Architecture Without Walls: Notes on the Home and Office, Atelier in situ and Discreet Logic (1999)

Graham, Robert. (1999). Architecture Without Walls: Notes on the Home and Office, Atelier in situ and Discreet Logic. Parachute, 96, pp. 11-15. Retrieved from https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3645327The commonplace that computer and communicational technologies have collapsed space should not be limited to the sense that they have contracted distance, but also that they overwhelm spatial division and compartments. This produces not only spatial dislocation (like the intimate cell-phone conversation held in the supermarket aisle) but also divisional collapse: as when a once-specialized space loses its dedicated purpose and becomes multi-faceted and multi-layered in its functioning. I’m thinking in particular of the tele-distanced, wired up, fully equipped and furnished oxymoronic “home office.” (It is a vestigial Marxist notion that new technologies are on the side of an emergent class.)

The artist has long been an emulated character type – if not of the life, well then, of the life-style. Artists have offered a model existence in that they succeed in eradicating the distinction and the gulf between work and life. It is a characteristic of artists that their relationship with their work is seamless and unalienated. While artists are free from command supervision, they seem indentured to their vocation. In fact, the life of the artist of legend is so bound with the work as to be inseparable and vital. Artists, it seems, never entirely relax. However long they lived, few would be considered ever to have retired.

While the original New York loft artists were attracted to the voluminous, high-ceilinged, large- windowed spaces for studios (they had divided up and individualized the large industrial spaces into smaller craft spaces), they also liked them as a place to live (thus the many zoning disputes). The large size of the lofts allowed the regions of work and rest to overlap. The model of the artist’s loft, the studio that is lived in, points simultaneously to the two work arrangements of the open office plan and the home office. As designs, both the loft and the open office are large undifferentiated spaces which are flexible to their ongoing function. They both exist to provide fluid project and task-oriented designs under adapting control. As accommodations, the loft and the home office keep work and domesticity close together and both away from larger and more centralized organizational spaces.

Nowadays, artists are considered the pioneer urban homesteaders of ex-industrial zoning. “Artists are a kind of pilot fish for gentrification. . . . They like cheap housing, they aren’t fussy about their surroundings, and yet they attract flocks of big spenders. . . . SoHo did not even have a name, let alone languid connoisseurs in expensive black clothes, until artists dis covered its industrial lofts.”1

The unified loft space — both a studio and a home — is the architectural analogue of an artist’s integrated life. It also represents the artist’s need to control and compose the surroundings and the conditions of production.

But the ideal meeting of work and life has become the threat of total industrialization. Just as the home/ loft represents the domestication of the work place, the home office is the industrial application of the home. (I am aware that for much of the world and for much of the past, the house has usually been the site of productive work — but this arrangement has not always been desirable. Customarily it has been the necessary means for people to function as both parents and workers simultaneously.)

From Soho to SoHo to SoHo. From London bohemian enclave and neighbourhood of immigrant restaurants to the Lower Manhattan area of artist-led industrial rehabilitation to the present day acronym for a burgeoning office equipment market: the Small office/Home office. By the year 2000 one out of every two houses in the U.S. will have an office.2 As the sign in a storefront window reads: “La-Z-Boy Office Furniture.”

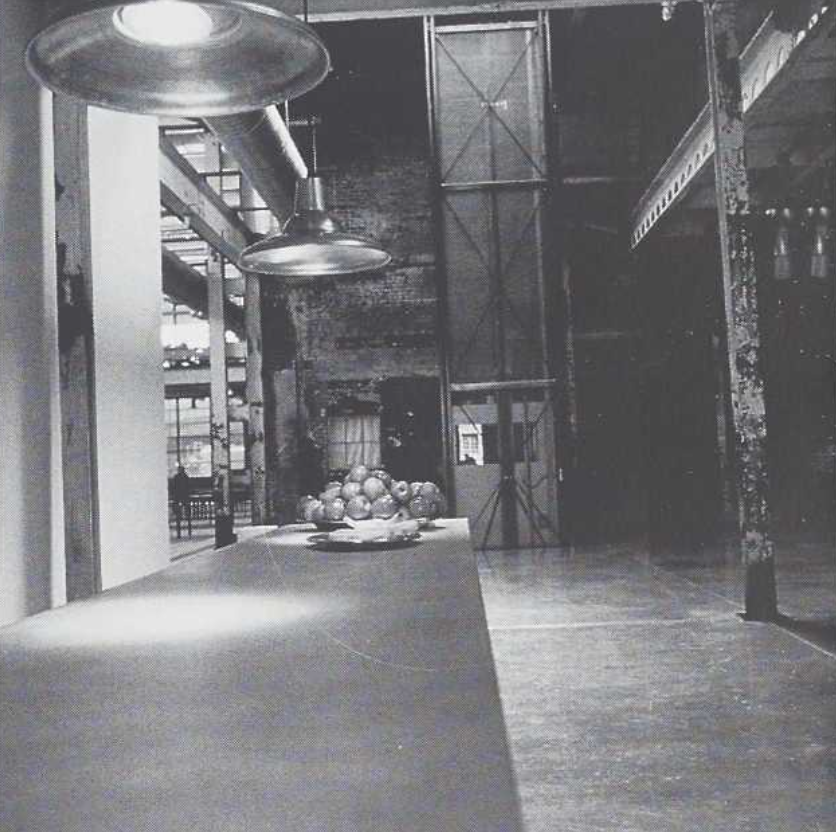

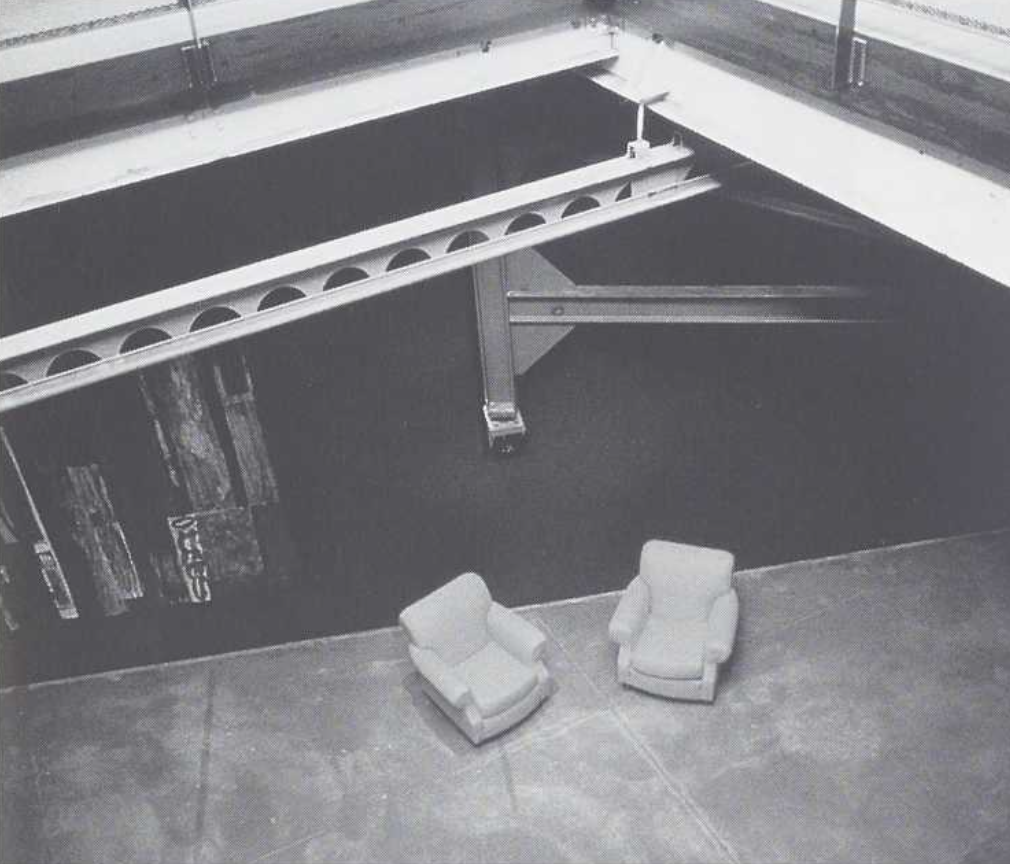

Discreet Logic is a software development company whose products include special-effects programs used in the making of films such as Titanic, Forrest Gump, Jurassic Park and others. Theirs is the very serious work of play — the amusement industry. The Discreet Logic offices are in a recycled shipfitters building (whose white painted signage “J. & R. Weir Boiler & Plate Shop, Machine & Pitting Shop, etc. ” still encircles the exterior brick walls and whose principal working material — steel — is the signatory material of the designers) in the old part of Montréal, near the river, the harbour wharves and the now disused grain elevators (which Le Corbusier thought so monumental).

It is a particular virtue of the Atelier in situ designers (Stéphane Pratte, Genevieve L Heureux and Annie Lehel) that they celebrate the history of the locations past and not attempt to erase or write completely over it.

NEC ad: “Success is no longer about where you work. That’s just geography. It’s about how you work.” Yet, geography matters. Though the nature of that geography is contentious. Rosalyn Deutsche’s critique of the knowable fixed space and a grounded geography is anti- foundationalist and against the resistance to difference and also a sometimes casually considered assault on ontological security.3

For Kafka, spatial flux and unpredictability were aspects of an arbitrary and inscrutable power: “And be sides, there are several roads to the Castle. Now one of them is in fashion, and most carriages go by that, now it’s another and everything drives pell-mell there. And what governs this change of fashion has never yet been found out. At eight o’clock one morning they’ll all be on another road, ten minutes later on a third, and half an hour after that on the first road again, and then they may stick to that road all day, but every minute there’s the possibility of a change.”4

“Indeed, even our mere architects, in their designs for habitual buildings, put on their mask of impiety and make interior spaces for infinite changeabilities. They have misplaced, somewhere on their drawing boards, the inherited knowledge of their craft, which was space made stable and trustworthy.”6 Symbol of exclusion and refusal – an architectural “No!” – the fixed wall is not a member of our current set of ideals. The more symbolically at tuned moveable divider, on the other hand, offers openness, in finite flexibility and possibility.

“There is a down side to working from home, according to William Michelson, a sociologist at the University of Toronto. Such employees may be more productive, but they work longer hours, spend far more time alone, and less time pursuing leisure activities than regular workers.”5

There remains a raw industrial patina of rust and unevenly painted steel. Some of the steel beams no longer bear anything but are instead suspended like industrial festooning. Functional piping, utilities and the elevator are all exposed. Everything is open and light. The furniture is monochromatic, functional and very comfortable. The effect is serious but casual — there is the dehierarchalized informality that you would expect in a contemporary software company. (Casualness of dress and conduct; sign of the domestication of work. However expansive they eventually become, computer software developers want to maintain that atmosphere of the basement or garage their work initially emerged from.) The ground floor work area is a large undivided space with a series of long parallel tables on which are computer stations, including high resolution monitors.

The ideal of a life in which the spheres of work and domesticity are joined in harmonious tandem, a 1 life in which the long-lived artist is often cited as an example, masks the frequent toxic effect: the traditional creative type is entirely committed to his work and either sweeps his family up in it or sweeps them aside. Thomas Mann’s son remembered with bitterness the silence that was enforced upon his childhood so that the old man could write in peace. Alexander Solzhenitsyn simply told his wife that a great writer could only afford his family so much of his time. Five percent, to be precise.

“For far too long the accent was placed on creativity. People are only creative to the extent that they avoid tasks and supervision. Work as a supervised task — its model: political and technical work — is attended by dirt and detritus, intrudes destructively into matter, is abrasive to what is already achieved, critical toward its conditions, and is in all this opposite to that of the dilettante luxuriating in creation.”7

Reviewing Lars Tunbjork’s photographs of New York office interiors, Her bert Muschamp noted that what overcame the Grid of the contemporary office plan was the Mess: the papers, wires and other overflow from function. How people messed around with the spaces they were allotted was how they reclaimed these spaces as their own. The Mess, he claimed, “takes over the function once performed by decoration.”8

In the case of the photographer Lynn Cohen, her camera constructs a Cartesian box of external regard applied to a space and volume which can then be visually measured. But this apparatus is put in a place that is inhabited, that is to say, a phenomenological space. The result seems discordant: the rooms have been made with non-visual criteria, criteria of specialized use and application, designed not to be looked at but to function.

In the mid-Nineties the Weir building was deserted and appropriated as a site for raves, which the police frequently raided.

In an earlier time, modernist artists presented life models which included a large component of pleasure and play. The reputation of contemporary artists seems entirely lacking in a ludic element. There is little of that light, childlike, purpose less play. Like many careerists, artists are reluctant to show any lack of seriousness or effort. Even what passes for leisure — exercise regimes, self-improving hobbies, extreme sports, or mass media entertainment — is entered into as work of another kind.9 When art and life or work and life are joined in the same space there is no alternate refuge region. Work comes to colonize the whole territory.

ALL PHOTOGRAPHS IN THIS ARTICLE ARE FROM DIANA SHEARWOOD’S PHOTOGRAPHIC SERIES, THE ZONE, 1997, COURTESY THE ARTIST. THEY WERE ORIGINALLY EXHIBITED AS LARGE-FORMAT INKJET PRINTS AT QUARTIER EPHEMERE (1998) AND HAVE BEEN PUBLISHED IN A BOOK OF THE SAME TITLE.

NOTES

1. Iver Peterson, “City’s Artists Are Its Pride and Some thing of a Pain,” New York Times, May 23, 1999, p- 28.

2. Barron’s, December 7, 1998.

3- Rosalyn Deutsche, Evictions: Art and Spatial Politics, Cambridge, ma:mit Press, 1996.

4. Franz Kafka, The Castle, trans. Willa and Edwin Muir, Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1968, p. 203.

5. Globe and Mail, October 5, 1998.

6. Philip Rieff, Fellow Teachers, New York: Dell, 1975, p. 21.

7. Walter Benjamin, Karl Kraus in Reflections, trans. Edmond Jephcott, New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1978.

8. Herbert Muschamp, “The Office’s Subconscious,” The New York Times Magazine, January 18, 1998, p. 32.

9. “Q: What are you looking at lately? A: I watch a lot of television for research. ‘Ally McBeal,’ ‘Buffy the vampire slayer,’ and ‘Xena the warrior princess’ are my favourite shows. I do ‘content analysis’ as I watch.” Daniel Pinchbeck interviews Sam Samore in “NY Artist Q & A,” The Art Newspaper, May 1999, p. 69.

Robert Graham is an art critic living in Montréal.

Selon l’auteur, les récents développements technologiques en informatique et en communication n’ont pas pour seul effet d’annuler la distance; ils bousculent également les normes de division spatiale, comme ces lieux distincts que sont la «résidence» et le «bureau». Avançant que les artistes habitant des lofts ont été les pionniers dans l’unification des sphères privées et de travail, cet essai examine cet idéal qui consiste à combiner espaces domestique et professionnel, de même que les effets parfois «nocifs» qui en découlent. Les bureaux des Discreet Logic, conçus par Atelier in situ, offrent toutefois un exemple stimulant de «simplicité non hiérachisée», où le sérieux et le moins sérieux coexistent.