Regions of Photography and War (1989)

Graham, Robert. (1989). Regions of Photography and War. In Le Mois de la Photo à Montreal, pp. 114-155.In the language of human (or time) geography, the life path of the war photographer marks a tense existence between inclusion and separation. Understood spatially, the activity of the photographer is located inside or outside demarcated zones which establish for the photographer and the work a position and a role. The photograph, and what we come to know of it, is the product of this activity and signals to us the conditions of its source moment. The literature of combat photography, which includes the memoirs, anecdotes, studies and fictions, is replete with images of closeness and distance, of regions and barriers and comments of how space determines relations and photographs.

While the war of policy and campaigns is deli berate and bureaucratic, the war in the fields is fierce, chaotic and runs counter to normality and the routine; as the arena of sudden destruction and death, it opposes and negates the civilizing aspirations of a secure community. For Michael Herr, in Dispatches, the cumulative effect of these stressed moments was to make Vietnam and “the World” antinomous terms: to be in the war zone was to be out of the world. Within the boundaries of a region of war, nonnative rules are suspended, murderous impulses find a home, and a taste for gore and violence can be tolerated.1 To become a soldier is to inure yourself to such an environment and to learn how to operate completely within it.

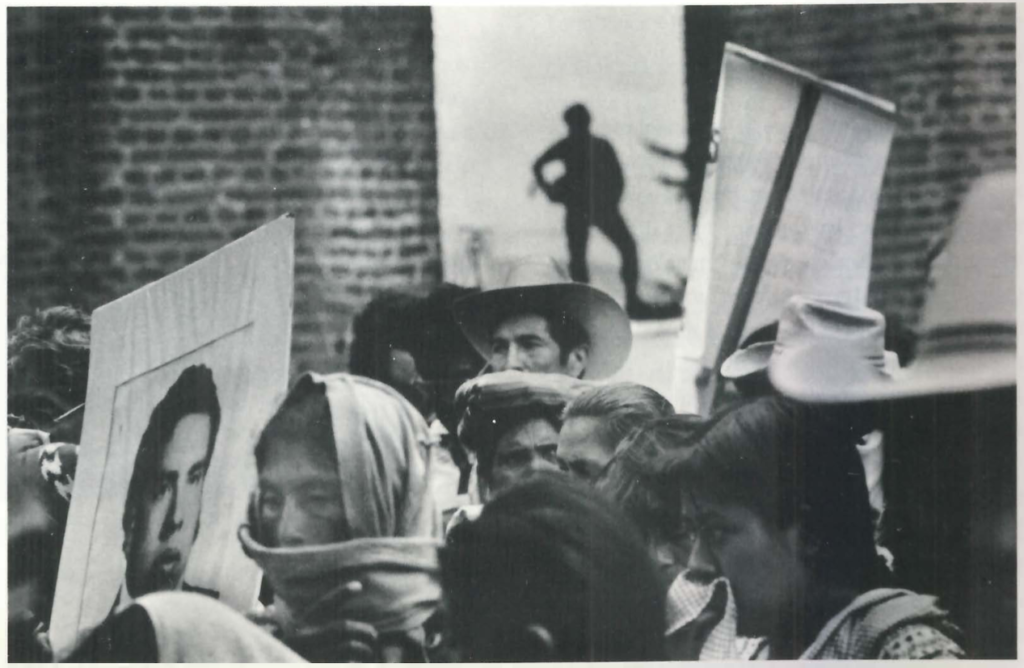

Physically within the milieu of the combatants, the photographer’s position is ambiguous: among the soldiers, but not of them. As go-betweens, the photographers represent those who are elsewhere, outside and in “the World”, but they also serve the combatants in recording and presenting their existence to that world. While photographer and soldier share locale, they are separated by the divergence of their respective “projects”, but joined together (and distinguished from the absent viewing public) in their common physical danger. The photographer’s situational condition then is to oscillate in alternating allegiances and identifications.

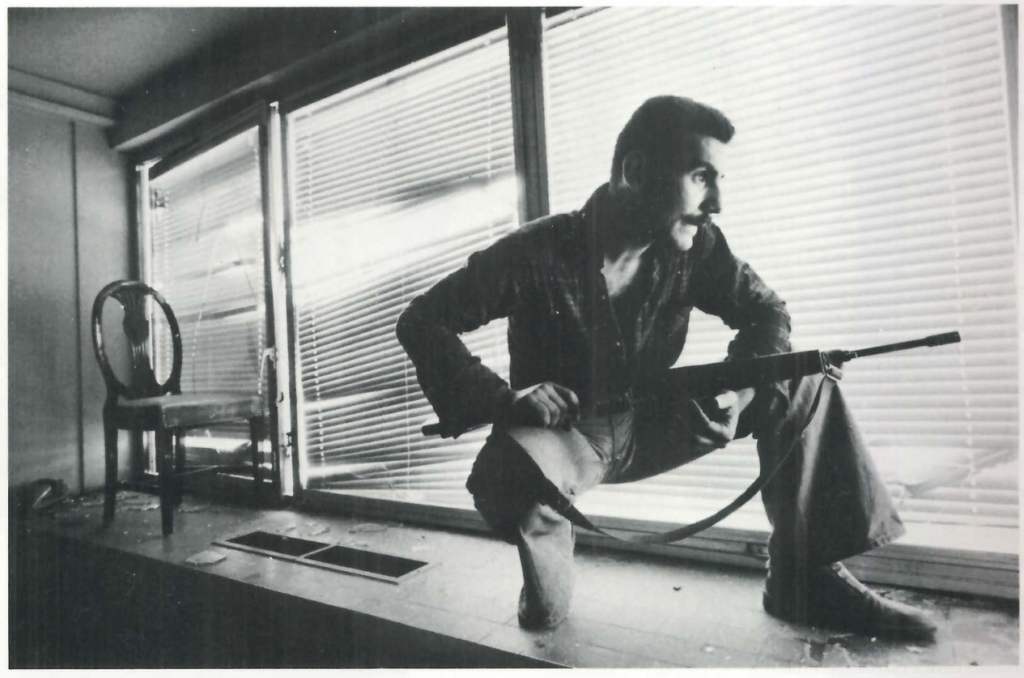

The site of oscillation is the edge, and the ambitious photographer will seek out the limits of the tested or permitted domain. The notoriously reck less Tim Page, “would go places for pictures that very few other photographers were going.”2 Robert Capa admonished that, “If your pictures are no good, you aren’t close enough.”‘ For Capa, the sign of the successful action photograph is the blur: “If you want to get good action shots, they musn’t be in true focus. If your hand trembles a little, then you get a fine action shot.”4 The photographer should be so close to the action of battle that he is himself shaken by it, affected by the battle but not part of it.

Of course, the most extreme edge of all is the line between the living and the not. “The best war photography is an epiphany of life and death…The image is striking because it captures the moment of death.”‘ By “capturing the moment of death”, the photographer is proclaiming how close he went to death, while returning from it – which many, like Capa, did not. It contributes to the power of combat photography, that whatever horror there may be in the scene of the photograph, the photographer was there and exposed to the same threat.

Some reporters step over the line and come to love the battle. They arm themselves and adopt the behavioural standards of the belligerent. “Vot I like eez boom boom. Oh yes.”6 The regular testing and straining of the ties with existence can become addictive. “I used to be a war-a-year man, but now that’s not enough. [ need two a year now. When it gets to be three or or four, then I’II start to be worried.”7

However much the photographer seeks to show closely a moment and a locale, he nevertheless remains separated from it. “[Peter] Arnett deter mined to “observe with as much professional detachment as possible, to report a scene with accuracy and clarity.” Above all, he never became involved in what he was reporting or photographing.”” Busily engaged in their professional duties, which is to say, what “the World” expects of them, the photographers cut themselves off from the activity of their human subjects. “Sometimes one feels like such a bastard”, said Larry Burrows9, and Michael Herr characterized the correspondent’s relationship as parasitic. Strip the heightened emotion from their choice of words, and what remains is their observation of the reporter’s distance, separation and difference.

Harry Beech, the photojournalist in Graham Swift’s recent novel Out of This World, offers the excuse: “A photographer is neither there nor not there, neither in nor out of the thing. If you’re in the thing it’s terrible, but there aren’t any questions, you do what you have to do and you don’t even have time to look. But what I’d say is that someone has to look. Someone has to be in it and step back too. Someone has to be a witness.” 10

The self-appointed witness has many opportunities to betray – exploitative of the soldiers in the extremity of their situation, or else playing upon the public with inculcating images on behalf of the journalism industry, government policy or political advocacy. Frequently enough in the commentary on war photography is the image of the camera as a weapon, or equated with a gun, and yet aimed at putative friends.

The photographers themselves consider that their task neutralizes them, and that their cameras are markers which separate them from those around them, and serve as protective talismans: “If you talk to news photographers who from time to time will put themselves in the most dangerous situations or amidst the most terrible scenes in order to get their pictures, they will describe a similar sensation. The camera seems to make them invisible, invulnerable, incorporeal…This heady sense of immunity will even compel them, over and above their obligations as journalists, to keep on visiting these zones of danger. Hey, don’t shoot me, don’t blame me. I’m only here for the photograph.””

As a personality type, the war photographer may be unfit for ordinary society. “Back in the World now, and a lot of us aren’t making it.”12 Yet the moral and existential posture of such a type can be useful to society, as the foolish, callous, candid figure able to, “…hold open the shutter when the world wants to close its eyes.”13 Such a photographer occupies a zone of consciousness so dangerous that irony, distanciation, ambivalence and oscillation may simply be the strategic characteristics necessary to make an untenable position tolerable.

Robert Graham, art critic

Notes

1 A fellow I once knew volunteered for the American forces in Vietnam, not for patriotic or ideological reasons, but because he had long wanted to experience killing a human, and the war offered him a legal opportunity to do so.

2 Michael Herr, Dispatches, New York, Ayon 1978 p:236.

3 Quoted in Susan D.Moeller, Shooting War: Photogra phy and the American Experience of Combat, New York, Basic Books, 1989,p:9.

4 Philip Knightley, The First Casualty: From the Crimea to Vietnam: The War Correspondent as Hero, Propa gandist and Myth Maker, New York, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1975, p:212.

5 Moeller, p: 19

6 Associated Press photographer Horst Faas, quoted in Knightley, p:408.

7 Donald McCullin, quoted in Knightley, p:409.

8 Knightley, p: 406.

9 Herr, p: 228.

10 Graham Swift, Out of this world, London, Viking, 1988, p:49.

11 Swift, p:121, In terms of regionalization, Swift’s novel stresses the effect of removal and distance in disembodied, unconnected vision.

12 Herr, p:243

13 Swift, p:92.