Here’s Me! or The Subject in the Picture (1990)

Graham, Robert. (1990). Here's Me! or The Subject in the Picture. In Thirteen Essays on Photography. Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography, pp. 1-12.

Graham, Robert. (1990). Voilà moi! ou Le sujet dans l'image. Dans Treize essais sur la photographie. Musée Canadian de la photographie contemporaine, pp. 1-13Even at the age of four or so, coming down the stairs with his nurse-maid… he would call out ‘here’s me!’

STAN GEBLERDAVIES

James Joyce: A Portrait of the Artist

The young James Joyce has provided me with more than a title. His exuberant self-announcement in celebration of his being, and of his being seen, also contains an illuminating childish grammatical slip: misemploying the objective case. To shout joyfully, “Here I am – the object of your attention!” is to state precisely the ways in which the subject operates in the field of the Other. Or, as French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan characterized the discourse of Jean Piaget’s egocentric child, “a case of hail to the good listener!” 1

For Lacan, the subject is a signifier within a topography of relational forces, not an entity, but a locus, the meeting point in a network of dynamic vectors. As the “I who counts”2 or the “I” who says “I…,” the subject/signifier is shifting and transient. Existing only in a present that quickly passes, the subject is constantly succeeded by a renewed subject in a new configuration of relations.

It is perhaps this very slipperiness of being which encourages psychocritical readings of the photograph to deal predominantly with the “scopophilic” urges of the photographer and the viewer, and to describe the photograph as an occasion for looking more than anything else . Paramount is the “I” who sees. Christian Metz, for example, has described the cinematic experience as a sequence of inscriptions in which the world imprints on the film , the projector projects on the screen, and the screenlight then illuminates the retina. The principal human activity in this model is that of the voyeuristic spectator, who identifies with and adopts the position of the camera lens. Transferred to the still photograph, Metz’s description brackets

the figure in the photo as “world” and neglects the dynamic process of exposure and self-exposure that occurs when a subject becomes a photo subject. While most people experience mass-media photo imagery as spectators, the experience of being a photo subject still merits examination.3

To be sure, we cannot re-illude ourselves into thinking that the figure in the picture is somehow co-present4 when we examine the photograph. The moment of that subject is past.

Even when the person photographed is still living, that moment when she or he was has forever vanished. Strictly speaking, the person who has been photographed – not the total person, who is an effect of time – is dead. 5

The camera does not provide, between figure and viewer, a subject-to-subject encounter of mutual observation or interaction. Nor can we renew naturalist readings of portraiture in which some interior identity is uttered and revealed through the picture. But the photograph remains and the subject in the picture knows that it will. The figure in the photo composes a “lasting impression.” Thus the photograph serves as the record of a meeting between a subject and an unformed future. Our existence as viewers is foretold and anticipated within the picture. As sitters we attempt to predict a distribution of the image, and we position ourselves accordingly. Both the figure and the viewer imagine and construct each other as potential beings. The viewer exists as an imaginary entity; or more properly, the abstracted viewer is plural and heterogeneous and, in some ways, objectified. Precisely because we cannot control the fate of our pictures there is discomfort: we address ourselves for the camera in the present and for an unknown context in the future.

In Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes describes his delicious anxiety at being photographed:

But very often (too often, to my taste) I have been photographed and knew it. Now, once I feel myself observed by the lens, everything changes: I constitute myself in the process of “posing,” I instantaneously make another body for myself, I transform myself in advance into an image. This transformation is an active one: I feel that the Photograph creates my body or mortifies it, according to its caprice …6

This passage helps us to mark out a common analysis of the photographic dynamic: in the hierarchy of photographic participants, the figure is the most passive, the one transformed and least in control, and, in short, all too often the victim of the encounter. Photographic thought has become irreversibly sensitive to this condition and seeks in its practice to compensate for, or to acknowledge in its analysis, the subversion of the subject at the moment of the photographic exposure. In logical extreme, Martha Rosler considered her unpeopled project, the bowery in two inadequate descriptive systems, “a work of refusal,”7 in not doubly harming derelicts by also showing them.

The legend of Marilyn Monroe leaves the suspicion that whatever the painful flaw in her life, it was somehow related to her superb skill as a photographer’s model. Feminist critiques of representations of the female body are well established on the basis that the objectification of the camera recapitulates and supports a position of male/viewer dominance. 8

Let me invoke Barthes twice more, first as he describes his defensive preparation for the session:

I lend myself to the social game, I pose, I know I am posing, I want you to know that I am posing, but (to square the circle) this additional message must in no way alter the precious essence of my individuality: what I am, apart from any effigy. 9

As soon as there is mention of a game, we know we are dealing with rules, conventions and codes. Thus the pose is a playful performance, a self-imitation. But, more seriously, it must not contradict an identity, a self-image. To become a photo subject is to transform oneself, to reconstitute oneself as an image. In posing for a photograph, the sitter must “write” with the body. But what the body says is a deceit and a betrayal of the “self “:

…each time I am (or let myself be)photographed, I invariably suffer from a sensation of inauthenticity, sometimes of imposture (comparable to certain nightmares). In terms of image-repertoire, the Photograph (the one I intend) represents that very subtle moment when, to tell the truth, I am neither subject nor object but a subject who feels he is becoming an object: I then experience a micro-version of death (of parenthesis): I am truly becoming a specter. 10

At the moment of the photograph the subject is dematerialized. The photograph is a representation of an “I” which is “Not-I.” The attempt to look “like myself ” produces a self-counterfeit. This inauthenticity – this gap – creates the sensation of fragmentation and objectification. The transformation by photography is the metamorphosis of a subject into an object. The copying of oneself (in the pose, in the reproduction) is a deathlike reification, a movement toward objectification, which gives the body the status of a carcass and the individual the character of a ghost.

And yet it would be a patronizing arrogance toward others and an unnecessary delimitation of our own powers as photo subjects if we were to typecast the figure in the photo as a specimen-like object of mastering regard. For even within the above analysis there remains the possibility of a subject, for whatever reasons, choosing mortification and accepting objectification. The figure in the photograph then becomes an agent, redeemed by an evident willingness to become someone else’s “signified.” Self-presentation is “negotiated” in two senses: navigating a threatening passage and also bargaining a contract. This is normally a strategic decision; and in acknowledging it we are also acknowledging an operating subject within the photographic discourse. In the “game” of the photograph there are several players, and the relation between them is shifting and uneven. In the “course” of a photograph, as the relations between players change, so will the position of the photograph change in the lives of the players.

Consider the passport photograph. The sitter is legally obliged to obtain a photographic portrait, and he engages a photographer (who is thus in a service position to the sitter) to produce the required image. At the studio, the photographer (for whom this work may be bread and butter – but also perhaps resented for being limited, dull and repetitive) directs and controls the sitter as to pose, facial expression and so forth. The photographer is paid, and the highly prescribed product (lighting, expression and cropping must fulfil certain guidelines, and the photo print itself must be of precise

dimensions) becomes a bureaucratic document. Having satisfied the authorities, the sitter’s citizenship is then officially acknowledged, and he receives the rights and protections due a passport holder. The community of viewers includes not only the functionaries in the passport office and at borders but also the friends and relations who will laughingly agree with the sitter that it is a terrible photograph. 11 (This attitude is not trivial; it represents a healthy distancing from state-delineated identity.) This description is about a photograph, but not of a photograph. The passport photo is evidence of interactional meetings between figures physically co-present or absent, though actively influential. It illustrates, clearly and simply, how certain kinds of photo images can be understood as more than visual artifacts.

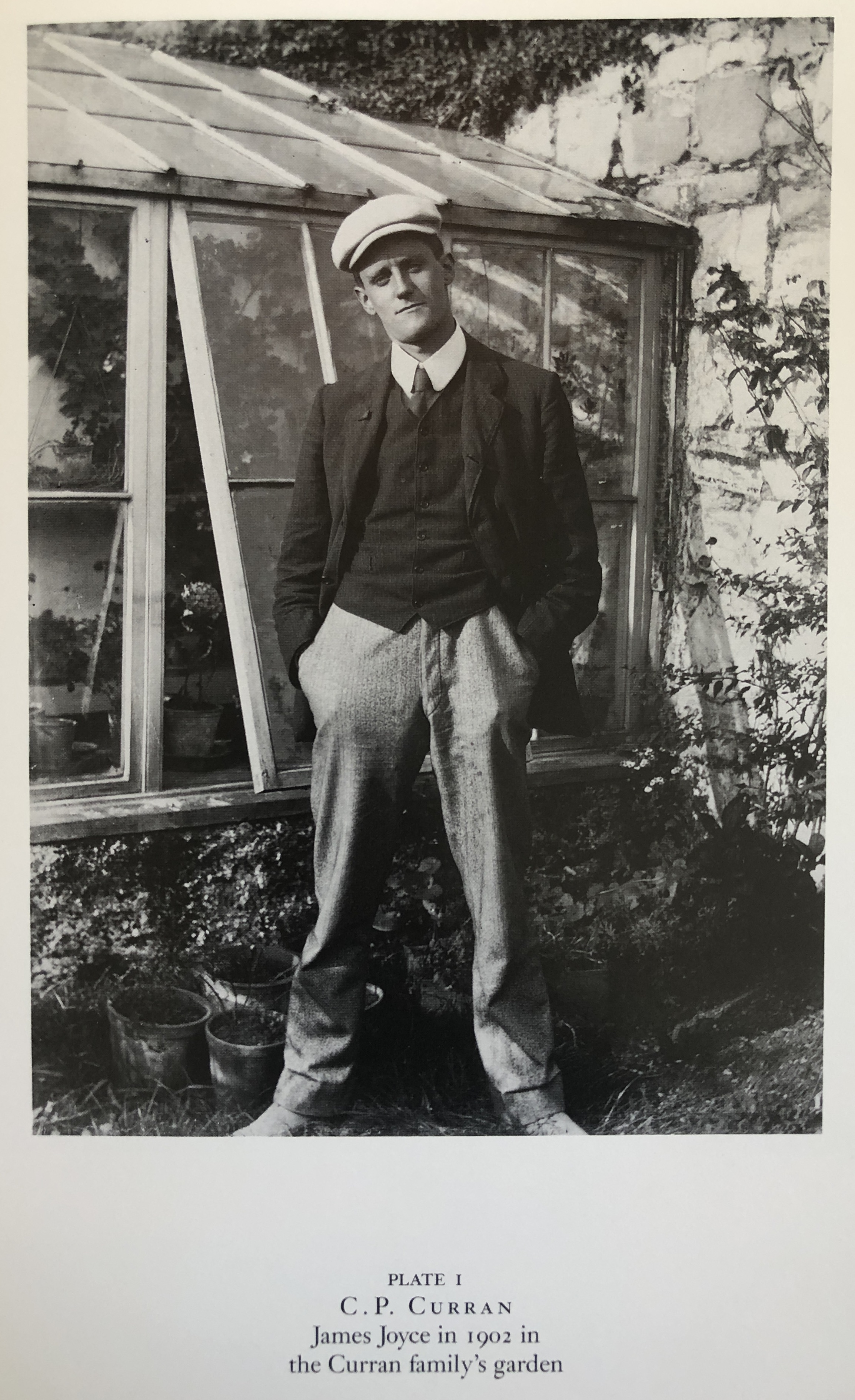

An older James Joyce left us with a picture (PLATE 1) taken by his friend C.P. Curran when Joyce was 20 years old: hands in his pockets, head cocked to one side, Joyce’s expression is almost glaring. And we have more: asked what he was thinking at the time, he replied, “I was wondering would he lend me five shillings.”12 In the same way that Joyce turned elements of his life into his art, and his own career into the stories of his artist-protagonists (Stephen Dedalus, Shem the Penman), this photograph comes to stand for the young predatory artist and his relation to the world. 13 As portrayed by Joyce, the artist borrows and steals from the world to transform (“forge”) the given material and make it his own. What the artist returns to the world is the celebration of his own genius.

To know that he was being read was more important to Joyce than he would have admitted. It was not that he demanded praise alone; he enjoyed dispraise too, and in fact all attention. He needed to feel that he was stirring an international as well as a Triestine pot, that the flurried life he created about him had somehow extended itself to the English-speaking world, so that everyone, friend or foe, was worried about him. He wanted to be commended, rebuked, comforted, but above all, attended to. 14

Yet Joyce’s notion of fame was archaic, and the lustre he sought would be won only through his work. As much as he enjoyed his portraits, their distribution did not contribute to the kind of prominence he would have considered important. To become, like Shakespeare, a radical shaper of the language itself, did not require photography. Photo fame would merely be the acknowledgment of his greater achievement.

Leo Brandy, in The Frenzy of Renown: Fame and Its History,15 describes the change that overcame the notion of fame after the advent of technologies of reproduction and diffusion. Traditional fame was the immortal glory bestowed upon those who held an office (such as king) or achieved accomplishment (heroes and artists.) The technologies of photography, printing and broadcasting have increased the quantity, breadth and effect of fame production. Public awareness and attendance have been broadened. If fame was once the result of some status or action, the wider net of celebrity now catches and enhances figures of otherwise little renown. The phenomenon of someone “famous for being famous” has developed; and even those of high standing now obtain attention beyond their due.

Of course, as Ben Franklin was one of the earliest to remark, the new power of visual media might also involve a new sort of entrapment for both the observer – under the sway of what he is so pleased to see – and the observed – imprisoned by the desire to be seen. 16

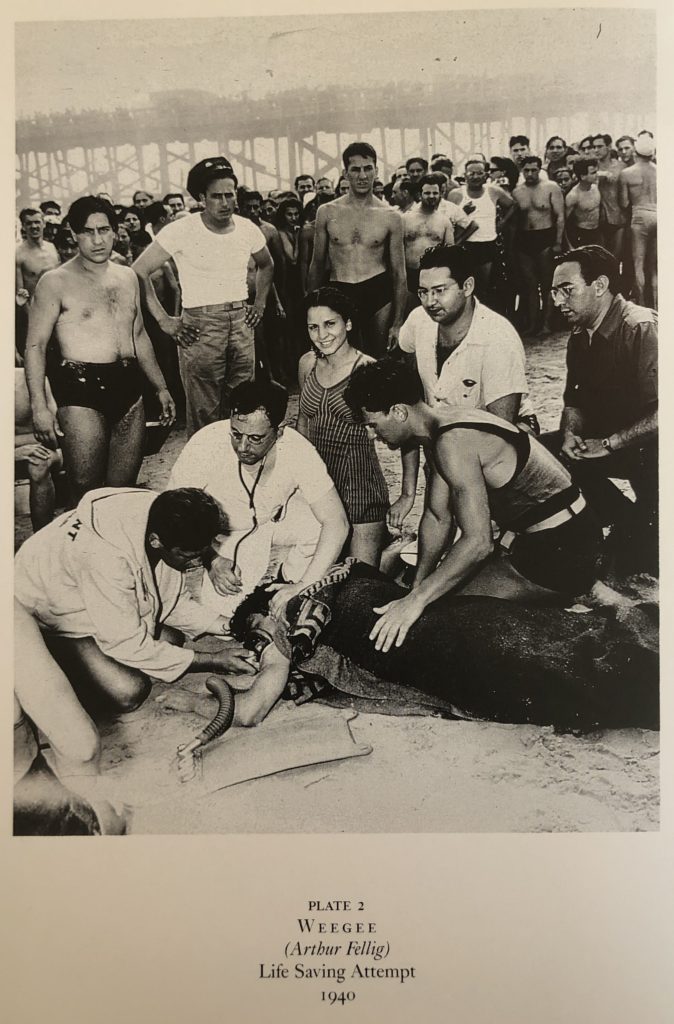

In such a psychic environment, fame, success and photography become entangled. In discussing the photograph Life Saving Attempt (PLATE 2), Max Kozloff says that Weegee contributes”to the reportorial mode a libidinal depth of his own.”17 (For libidinal, read penetrating.) The woman in the photograph has been caught in a parapraxis, a gestural “slip of the tongue” provoked by the camera’s own presence. Implicit in the reporter’s attention is the command to smile. She was helpless to resist. In daydreams she must have rehearsed for this moment, and in pure stimulus-response her training showed. The extreme inappropriateness of her pose is a measure of the camera’s determining power in setting a context that can violently conflict with the lives it enters. In the clash of contexts her relationship to the scene of the accident was overwhelmed by her spontaneous connection with the photographer.

Her mistake was wanting to please; and if a slip is still a choice, her decision to smile betrayed her desire for the nourishment of attention. The wish to show oneself is also a wish to “see someone looking at me,” to have one’s existence confirmed. Fame moralists tend to dismiss this sort of dependency as a pathetic vanity. But vanity itself, as vanitas, has a more profound history as the desperate manoeuvre to defy death armed only with temporal means. The immortality of great achievement is no different, for both petty and grand vanities are no more substantial than a wish.

When fame is domesticated and internalized in the fantasy world of the individual, pathological behaviour can break out. “Star” figures gain cult status while simultaneously becoming intimately (if artificially) familiar to their followers through the mass of detailed information provided about them. Braudy calls this the “democratization of fame” in the sense that fame becomes an experience potentially available to anyone and the celebrated become identified as the creatures of their audience. Claims upon fame and the famous become perceived as more broadly exercisable – and the resulting disappointment more widespread.

The phenomenon of the “celebrity stalker,” such as Ronald Reagan’s assailant John Hinckley or John Lennon’s assassin Mark Chapman, illustrates how mass-media relations can recapitulate or be redesigned as direct and personal emotional relations. The celebrity stalker usually stalks in two ways, first by claiming the intimate attention of some famous figure. Considering all other fans so much ticket fodder, he attempts to force the celebrity to acknowledge the stalker’s own specialness. He is, in his lights, both the biggest fan and, transcending that, the one who will save the celebrity from the distresses of fame. The stalker, more than anyone, “knows” the star and shares a destiny with the star. 18

But he also seeks fame for himself. Fame will be the acknowledgement of his power and will give him the status needed to become the celebrity ‘s consort. Hinckley ‘s attempt to assassinate Ronald Reagan was a kind of love tribute to movie star Jodie Foster. It would both get her attention and give him a fame equal to or greater than Foster’s own.

The celebrity figure in the photograph is, for the stalker, a split-off and idealized object. “Some people deal with their incapacity (derived from excessive envy) to possess a good object by idealizing it.” 19 Melanie Klein’s model of the envious soul provides us with a way to describe such media fixations. The celebrity, who is surely transformed into an object, can be manipulated symbolically by the stalker in any fashion he determines. Alternately loving and persecuting, the celebrity is particularly fit to be a split-off object because of the various ways in which media technologies create an illusion of closeness where really there is distance.

The damaged subject is caught up in psychotic projection and introjection, attempting to break through the pane of recognition against which his face is pressed. While desperately trying to cross over to the other side, he is also disparaging the figure of established acclaim. Apparently Chapman’s principal complaint against Lennon was that he was a hypocrite and a phoney. Yet what Chapman found memorable about the few moments before the killing was that John Lennon was looking at him. Chapman had succeeded in vaulting the counter to join the famous figure of his obsession in physical co-presence and intersubjectivity.

This kind of confusion exists in the political realm as well. Mahmoud Mohammad Issa Mohammad is a Palestinian immigrant to Canada who faced deportation for having entered the country without revealing his conviction in Greece for an attack on an Israeli jetliner in which one person died. When interviewed, he described the incident as “an advertisement, just to publicize to the world, to make the world understand what was going on in the Middle East…”20 It is an astonishing commentary on what currently passes for war and politics when death and destruction are considered merely the tools of publicity. Acting in front of and for the camera has become the contemporary mode of political representation, and the power of attention has become confused with the power to affect. Such confusion is not limited to outsiders. In a review of former White House Press Secretary Larry Speakes’s memoirs, Nicholas Lemann wrote:

The allure of the White House is not captured accurately by the word usually used to convey the essence of upper-level Washington life, power. Speakes was not powerful, exactly….Fame comes closer than power to describing what Speakes loved about the White House (he mentions proudly that even Mikhail Gorbachev “knew me on sight”), and he also loved the sense of being at the center of things – the phone rings all day long, and whatever one is working on is of intense interest to hundreds of reporters who presumably reflect the raptness of tens of millions of readers, listeners, and viewers. 21

The movement of photographic imagery into mass media, and the identification of media success with general success, power and enhancement, have fostered the belief that photographic representation is basic to nearly any form of enfranchisement. The camera, as a tool of empowerment, requires those who seek power to employ themselves strategically as photo subjects.

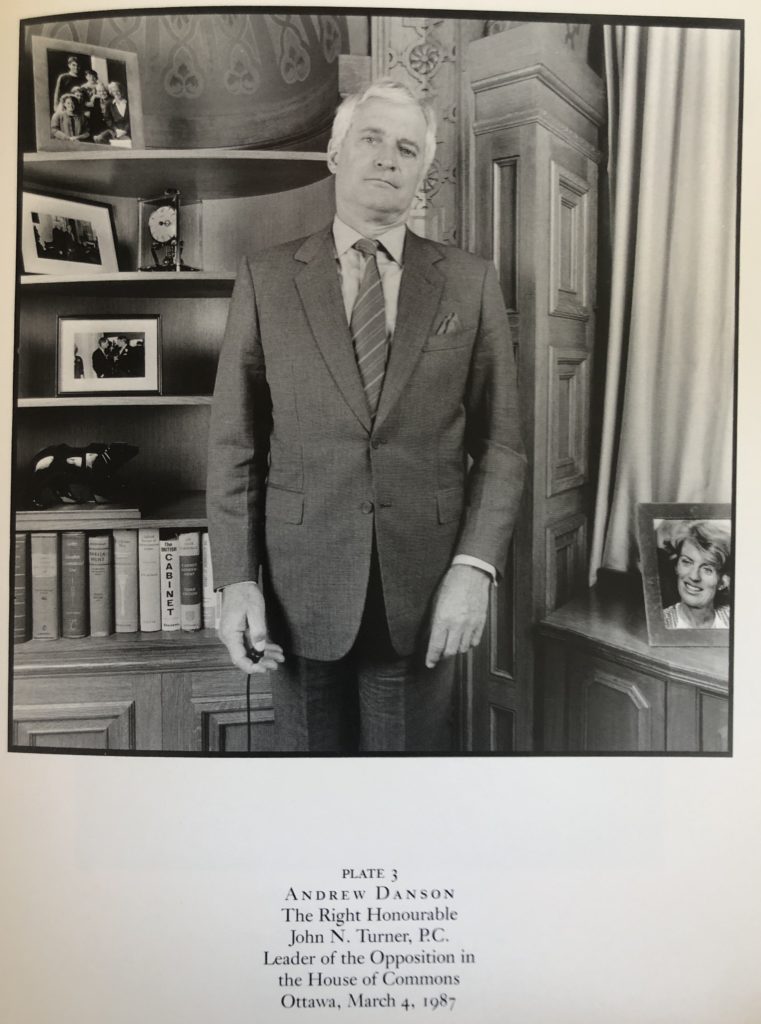

Andrew Danson’s Unofficial Portraits 22 project is a curious attempt to short-circuit the process of political representation by establishing a “holiday” context in which the normal expectations of behaviour are suspended. He would set up his camera in the office of a Canadian politician, hand over the remote shutter release, and leave the room.

The politician was then to take eleven self-portraits. According to Danson, most politicians accepted his invitation, a few declined (Rene Levesque, Jean Drapeau), and one actively courted him: Brian Mulroney. The terms of the situation invite the politicians to relax and have fun; it is almost commanded of them. The subtext calls for them to behave “out of office,” that is as private individuals who have shed their official, and representative, mantles. But not all of them could (PLATE 3). The pictures occupy a zone that one might call “at home in the office,” an occasion for people who, in varying degrees, are comfortable with their status as representatives. As Hans-Georg Gadamer elaborates:

…it is because the ruler, the statesman and the hero must show and present himself to his followers, because he must represent, that the picture gains its own reality . …When he shows himself he must fulfil the expectations that his picture arouses. Only because he has part of his being in showing himself is he represented in the picture …. If someone’s being includes as such an essential part the showing of himself, he no longer belongs to himself. For example, he can no longer avoid being represented by the picture and, because these representations determine the picture that people have of him, he must ultimately show himself as his picture prescribes. 23

At first John Turner refused Danson’s offer. But the photographer happened to meet Turner’s wife Geills on an airplane, and she was able to convince Turner to take part. Her own image appears in the lower right-hand corner of the photograph, where an authorial signature might go. Turner is often considered uncomfortably ambitious, as if his drive were coming from outside himself. One observer has described him:

From nervous worry and excessive adrenaline, he was forever clearing his throat, adjusting the knot of his tie, licking his lips, barking at his own jokes, chewing a breath mint, and scrunching his eyes….friends wanted to shake him by the shoulders and yell, “Come on, John, relax! You don’t have to impress me.” Yet Turner seemed incapable of relaxing because there was always his God, his mother, and himself to impress. 25

Turner’s initial resistance to the project and his stiffly suspicious appearance in the photograph can be understood in the light of his divided “impression management.”26 As a politician he must show and give himself to his public; but the satisfaction he obtains from public life is to be shown and given to a smaller and more crucial audience: “his God, his mother and himself.” Public success then becomes merely a means to something much more personal. While he dedicates himself to the public, that public must, in turn, serve him in meeting a quite private purpose.

There is also a shelf visible in the Danson picture, and on that shelf is a photograph of Turner meeting with Robert Kennedy. Turner reportedly had an entire wall in his former law office hung with such pictures,27 common enough among politicians and others. However else the pictures are prized or employed, this practice suggests a trebly articulated self-display: look, it says, I’m being looked at (by the camera) when meeting with (and being looked at by) the renowned.

Danson’s work affirms the necessity of politicians to be represented in ways acceptable to themselves. To read through the self-objectification of the photograph is to recognize the self-symbolization that the figure constructs. This construction occurs under conditions of conflict in which the figure is struggling for representation. The photograph provides a point of conjunction for a complex of strands in a web of intersubjectivities. Aside from questions of viewer empathy, or true or false identity, both of which are issues of trust, rests primary observation – to see the wanting of the agent who wants to be seen.

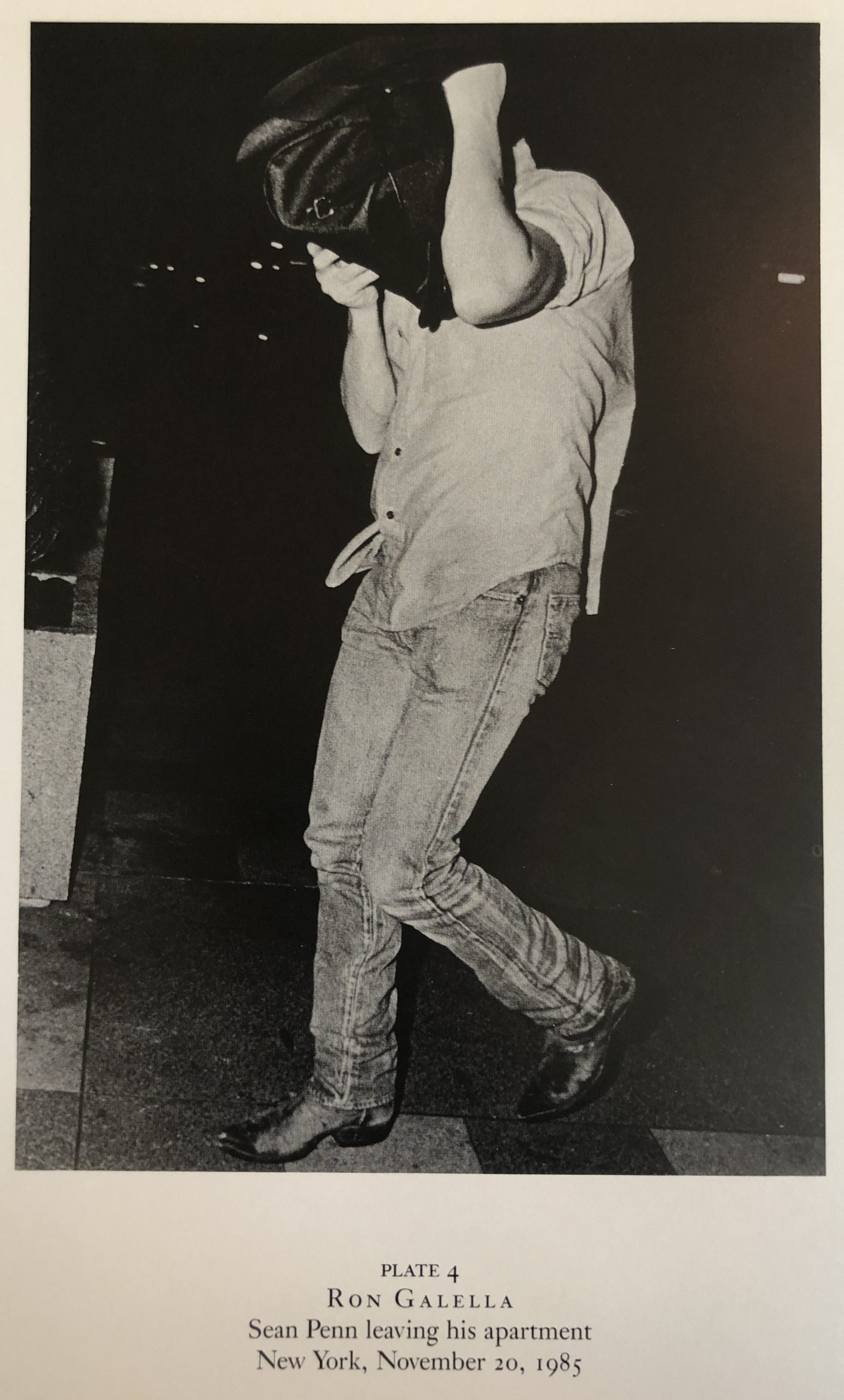

Joyce’s aggressive artistic claims, the momentary flash of news-photo glory for the woman at Coney Island and John Turner’s solemn obligation to sustain representation are all ordinary instances of the exhibitionist strategies of subjects within pictures. The pathological and the desperate are somewhat more extreme examples of those who, insufficiently nourished, will do anything to get into the frame – to become the objects of others’ regard. For them, even notoriety is better than neglect. In terms of communicational hygiene, the tactical necessity or psychological compulsion for self-exhibition is countered by modesty (PLATE 4).

In the biblical tale shame also came from the crime of devouring, which in my interpretation was oral castration. Shame is opposed to exhibitionism. Language reveals the oral tinge of exhibitionism as a fantasy or wish to be devoured….Adam in developing shame did not protect himself so much from oral-sadistic voyeurism as from his own self-destructive wish to be devoured….The self-destructive passive element of exhibitionism tends to be more repressed than the oral sadism underlying voyeurism. 28

The subject in the photograph enters into an accord: in exchange for being sacrificed to and absorbed by the camera, the viewing public (which may be as small as a family) offers significance to the subject. Barthes admitted one exception to the determining signification of being photographed: only a context of extreme love allowed his body to find its “zero degree” and erased the “weight of the image.”29 Perhaps only for his mother, he thought, could he stop posing.

But then, perhaps only for his mother would he give up resisting.

NOTES

1. Jacques Lacan, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psycho-analysis, ed. Jacques-Alain Miller, trans. Alan Sheridan (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1979), p. 208.

2. Ibid., p. 20.

3. Two related areas of photo subjecthood have been opened up. The first is the investigation of the subject as exploited victim within a system of image production, which, to use Walter Benjamin’s phrase, turns “misery into a consumer good.”

The second is the historical study and ongoing monitoring of the application of photo-technologies for surveillance and identity processing by government, police and industry.

In another vein entirely, Jo Spence’s “photo therapy ” explores the possibilities for individual and social-health enhancement through the activities of the figure in portraits and self-portraits. See Jo Spence, Putting Myself in the Picture: A Political, Personal and Photographic Autobiography (London: Camden Press, 1986).

4. In sociology, the notion of co-presence is used to emphasize the interactive character of mutual physical encounter when the body of an experiencing self meets another. See Anthony Giddens, The Constitution ofSociety: Outline ofthe Theory ofStructuration (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984), p. 64.

5. Christian Metz, “Photography and Fetish,” October, 34 (Fall 1985), p. 84.

6. Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981), pp. 10-11.

7. Martha Rosier, “in, around, and afterthoughts (on documentary photography)” in 3 works (Halifax: The Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1981 ), p. 79.

8. As usual, there are the exceptions. For example, Caught Looking: Feminism, Pornography & Censorship is a feminist celebration of diverse smut. Yet, as the title suggests, it remains mostly concerned with observer rights. See Kate Ellis et al., eds., Caught Looking: Feminism, Pornography & Censorship, 2nd ed. (Seattle: The Real Comet Press, 1988).

9.Barthes, pp. 11-12.

10. Ibid., pp. 13-14.