War/Photography: Images of Armed Conflict and Its Aftermath (2014)

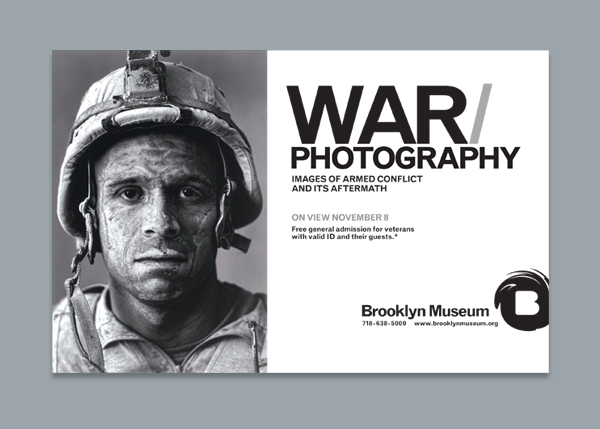

Graham, Robert. (2014). Review of War/Photography: Images of Armed Conflict and Its Aftermath, Anne Wilkes Tucker and Will Michels, with Natalie Zelt; with contributions by Liam Kennedy, Hilary Roberts, John Stauffer, Bodo von Dewitz, Jeff Hunt, and Natalie Zeldin. RACAR : Revue d'art canadienne / Canadian Art Review, 39 (2), 113–115. https://doi.org/10.7202/1027754arWar/Photography: Images of Armed Conflict and Its Aftermath, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, (11 November 2012–3 February 2013), The Annenberg Space for Photography (23 March– 2 June 2013), Corcoran Gallery of Art (29 June–29 September 2013), Brooklyn Museum (8 November 2013–2 February 2014).

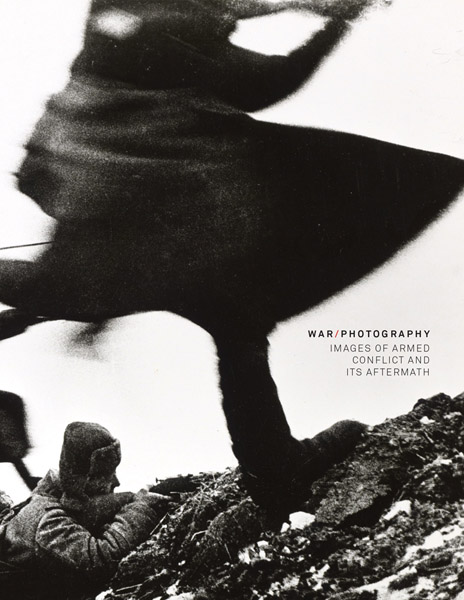

Anne Wilkes Tucker and Will Michels, with Natalie Zelt; with contributions by Liam Kennedy, Hilary Roberts, John Stauffer, Bodo von Dewitz, Jeff Hunt, and Natalie Zeldin, War/Photography: Images of Armed Conflict and Its Aftermath, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2012. Distributed by Yale University Press, 612 pp., 179 colour and 364 b/w illustrations, $90, ISBN: 9780300177381.

Imagine a Venn diagram in which one circle represents the set of all things photographic and the other circle the set of every human conflict, from limited regional insurrections to totalizing global wars, since the eruption of the Mexican- American war in 1846 to the Arab Spring of 2011.

The physically massive exhibition War/Photography: Images of Armed Conflict and Its Aftermath and its accompanying catalogue occupy the intersection of those two circles. From this vast area the curatorial team of Anne Wilkes Tucker, Will Michels, and Natalie Zelt have chosen a rich sampling of nearly five hundred photographs, plus a selection of albums, magazines, cameras, and other photo-related objects, including supporting ephemera such as maps, a G.I. Joe doll, a comic book—which, following contemporary practice, once vitrined, become artifacts. While there are many examples of photojournalism, often legendary, there are also pictures from official, commercial, anonymous, personal, and vernacular sources.

The curators present this material not as a historical chronicle but as a taxonomic survey of conflict imagery types. As Anne Wilkes Tucker describes it, the collecting process was at first indiscriminate and without explicit goals, but once it was completed, “certain patterns nevertheless begin to emerge…thus the structure of this book and exhibition…is organized…according to the most common and meaningful of the recurring types” (3). Such a taxonomy schematizes phenomena while highlighting the archetypal and repeated, seemingly habitualized patterns of learned behaviours, marking the temporal movements from “The Advent of War” to “The Fight” and its aftermaths on to “War’s End” and “Remembrance.” In the initial installation at The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the exhibition space was partitioned into twenty-nine sections, providing a scaffolding for the elaboration of each particular theme and its portrayal of the range of photography’s wartime applications. The audio guide often contributed an affective counterpoint, reminding us to consider feeling, delight, and horror, as well as the aesthetic dimension of the material, which is, after all, the traditional role of the fine art museum.

The historical period considered here, the entire era of the camera’s existence, begins during what economic historian Douglas W. Allen identifies as the era of the “Institutional Revolution” which, between 1780 and 1850, caused the world to emerge as a more measured, organized, predictable and man- aged place; indeed, even war became more regularized and subject to routine procedures.1

The display format of the exhibition underlines the consistent shape of the conflicts themselves: that is, for the most part, Clausewitzian bipolar wars, popularly supported, between discrete states battling over demarcated contested terrains. The photographic work and the elaborate back stories included in the accompanying texts together testify to the massive industrial scale of institutional war (of which Edward Steichen’s naval work is particularly indicative). Ernst Jünger, writing on war and photography in WWI, suggested that “a collection of such optical documents opens the way for a valuation of war not only as a succession of battles, but, in its essence, as labour as well.” In this case, “industrial” means not only heavy machinery, but also the administrative apparatus and organizational practices of modern industrial management. Two rhyming pictures, taken more than forty years apart, show the consistency of administrative requirements: Al Chang’s 1950 A grief-stricken American infantryman whose buddy has been killed in action is comforted by another soldier. In the background a corpsman methodically fills out casualty tags, Haktong-ni area, Korea, and David Turnley’s 1991 Iraq contain a grieving soldier in the foreground while another soldier, like a recording angel, is dispassionately filling out a form in the back.2

The battle for Iwo Jima has its own section, with Joe Rosenthal’s 1945 Old Glory Goes Up on Mount Suribachi, Iwo Jima, as the centrepiece of the exhibition. Possibly the first print of this image produced, it is a murky little thing and yet is the germ (acquired by the MFAH in 2002) of the museum’s new war collection and of this subsequent exhibition and publication. Although the image suggests a conclusive, vanquishing moment, the battle was in fact not over and some of the men in the picture would not survive. Yet it would be difficult to overestimate the picture’s receptive potency and expansive after- life, even if it initially represented more an aspirational goal image of an unfinished war rather than a realized triumph. Along with the surviving soldiers, the image (with its many iterations) quickly became enlisted back home in a substantial bond drive effort. In his essay “The Instrumental Image: Steichen at War,” Allan Sekula wrote of the instrumentalization of photography, of which, I suggest, the militarization of photography is one instance. Such purpose is a form of soft photo-pragmatics, which encourages morale, inspires behaviour, and also sup- ports the functions of public relations, propaganda, and dis- information. Hard photo-pragmatics, on the other hand, is the weaponization of photography whereby the camera is used for intelligence gathering, surveillance, target calibration, and the identification/control of populations, in both domestic and occupied territories.3 For above all, “The military now perceives information technology, photography, and film as part of the battlefield” (285). It is an aspect of this exhibition/catalogue to identify photographs that have been narrowly applied to “military perspectives and priorities” and to expose them to fresh examination. While the catalogue does not refer to Sekula, the exhibition does provide material for an instrumentalist discus- sion. As Tucker can claim, “This project is a platform from which other inquiries can spring” (7).

Toward the end of this survey of the shocking and the ordinary (more than once the catalogue cites the adage about war being 99% boredom and 1% sheer terror), in the Remembrance and Memorials section, there is an elegiacal envoi, Simon Norfolk’s threnodic chromagenic tableaux, the 2004 series Normandy Beaches: We Are Making a New World. After all that we have been shown in the exhibition, the shorelines in these images, though without human figures, certainly seem haunted.

Despite War/Photography’s seriousness, quality, and interdisciplinary breadth, its inclusion within the discourse of photographic history is problematic, for the project may find itself on the far side of an axiological divide. Among the catalogue’s contributors are military historians, who, as an academic group, consider war a normal fixture of history, approach ordnance with curiosity and pleasure, and consider soldiering among the highest of human pursuits. One of the photographs in the exhibition, Kenneth Jarecke’s 1991 Incinerated Iraqi, Gulf War, Iraq is a horrific picture of a blackened, carbonized man; it is also a picture the Associated Press found too disturbing to distribute in the United States. In a discussion in the catalogue, Jeffrey Wm Hunt, a military museum director and historian, recounts saying to an audience, “Let me tell you what that picture really is—victory. That is what victory on the battlefield looks like” (282). His is what might be called the erotic stance toward war, which admits of the possibility of war’s satisfactions. The erotic suggests implicit sexuality as, when discussing the popularity of the picture of Australian soldiers by Alexander Evans, Field Guns in action, Gallipoli, Ottoman Empire (1915), Tucker acknowledges the “appeal of the fine male bodies.” But it can also include fraternal love, meaning-finding, and physical excitement. Within the critical photographic community, on the other hand, there is a well-established position, following from Susan Sontag’s Regarding the Pain of Others (2003), which resists the phenomenon both of conflict, identified as atrocity, and of its imagery, identified as “the traffic in pain.” Helpless in the face of photography’s impotence to end war, photographers and commentators seek alternative forms of resistance that do not simply energize the problem of conflict. Geoffrey Batchen, in his contribution to Picturing Atrocity: Photography in Crisis, proposes borrowing the strategy of Martha Rosler’s The Bowery in Two Inadequate Descriptive Systems (1974–75) in refusing to doubly victimize the victim through display. Calling for an intentional and purposeful looking away (“looking askance”), he cites artists who “eschew the picturing of any particular moment or incident and instead immerse us in a visual experience that is at once calm and implacable, empty of ‘content’ but all the more powerful for it” (238). Here he could be describing the Norfolk Normandy pictures. This solution may bring moral relief to some image-makers and viewers, but such a position may be seen as an abdication: for as photography critic Susie Linfield writes in The Cruel Radiance: Photography and Political Violence, “It has become all too easy to avert one’s eyes; indeed, to do so is considered a virtue.”

Yet, formally and tactically, indirect looking may also be a sufficient approach to the conflicts of our time. Joe Rosenthal’s flag-on-a-hilltop picture represents a strategy that is no longer available to us. Such overt symbolization, as the embarrassing and repudiated effort to cover Saddam Hussein’s face on his statue in Baghdad in 2003 showed, seems absurd. The Iwo Jima picture does not function as illustrative of current military orientation. Western soldiers no longer fight for a flag, nor for a piece of ground, but for each other (among supporting representations of this is Tim Hetherington’s Infidel). Camaraderie and loyalty become their standard. They are not looking up toward the flag or the peak, but sideways toward and for the sake of their buddies. States harness the fight of soldiers, but once in place the soldiers are actually fighting on behalf of each other. As Hunt concludes, “Your unit is your family” (283).

Post-modern, or asymmetrical, warfare, often during an insurgency, is not bipolar and does not present a clear front. Instead of a demarcated ground, the goal is a population that is also the battleground (“hearts and minds”) and displays no markers identifying ally or enemy. Suicide bombers may be present. Snipers and landmines permeate the sphere of battle, and with the addition of drones and stealth missiles, danger is all around and environmental.4 As contemporary military theorist Emile Simpson describes it in his War from the Ground Up: Twenty-First-Century Combat as Politics, in such 360° warfare, “actors tend to act in a kaleidoscopic manner.” The battlefield is no longer a Euclidean topography of clearly drawn lines, but a topology of ambiguous boundaries and shifting definitions of interior/exterior space, not representable with single point- of-view vision. Thus, there is a correspondence between the manner of fighting and the manner of photographing. Look- ing askance or looking obliquely may be what is required. The conflict itself is not visually portrayable, for visibility only occurs afterwards and indirectly with the plain forensic evidence of damaged landscapes and victims’ remains. The photographer Louie Palu, whose work is included in the exhibition, became exhausted by the inchoate demands of the fighting itself and now only photographs soldiers after they have left the battle, “debriefing” them through their appearances—frontal headshots of the expressions, dirt, sweat, wounds, and exhausted eyes peering back at the photographer.

The organizers of this exhibition and its catalogue have produced a work of synthetic curatorship that successfully straddles the domains of recent military history and photographic discourse. Having moiled the archive, the curators have selected materials which evidence the ways in which photography has historically been used in war by the military, by photojournalists, and by participants and bystanders caught in war’s way. And in some cases, art has been a byproduct. For both military and photographic history, the project serves as a graphic testament to war’s organized destruction and administered death, and to the learned, mediated, and repetitive character of much past conflict.

Robert Graham, Independent scholar

Notes

1 Douglas W. Allen, The Institutional Revolution (Chicago, 2012).

2 Allen argues that it is the establishment of such methodical documentation that removes war from the feudal model based on honour and trust and transforms it into the modern institutional version reliant on oversight, measurement, and record keeping.

3 In 2003, pictures of the Iraqi government leadership were printed on playing cards (with Saddam Hussein as the ace of spades) and distributed to the soldiers to help identify them. War/Photography, 40.

4 Peter Sloterdijk calls this condition “atmoterrorism” in which the atmosphere is weaponized by the threat of toxins and the environment itself becomes feared. See Terror from the Air (Los Angeles, 2009).