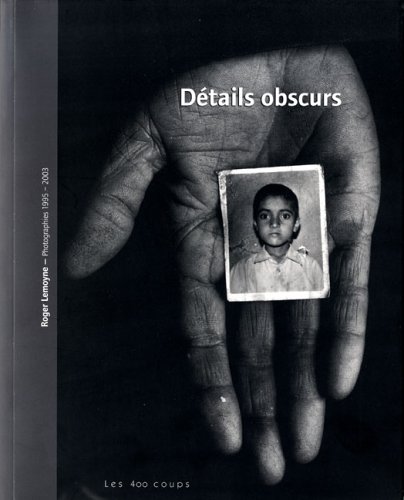

Seeing to Care: Roger Lemoyne Photographs 1995-2003 (2005)

Graham, Robert. (2005). Seeing to care: Roger Lemoyne photographs 1995-2003. In R. Lemoyne, Détails obscurs. Les 400 coups.Détails obscurs

Un portrait des victimes des guerres d’aujourd’hui

Photographies de Roger Lemoyne 1995-2003

Shadow Detail

A portrait of the victims of today’s wars

Photographs by Roger Lemoyne 1995-2003

English version

Seeing to Care: Roger Lemoyne Photographs 1995-2003

by Robert Graham

Initially, Roger Lemoyne began his photographic career as a traveler with a degree in film-making who took up photography for the independence it seemed to offer. Returning home he found that he could sell his pictures and this new found market gave him a reason (and means) to travel again. As a freelance photographer he could choose his destinations and his pace. The photography and the traveling supported each other.

Moving toward the edges of regions of conflict, Lemoyne discovered his mission. It was Africa, especially the Congo for three weeks in 1997, which had the most stirring effect on him. It was in Africa that Lemoyne found what he needed to do and to which he will be returning to chronicle the brutal experience of what he calls “war-affected” children. Of his work photographing such children, Lemoyne has written, “I did not set out to cover conflicts in this light. The theme of war’s civilian victims seemed to be thrust upon me as I traveled to areas of conflict.” Institutional identity is formed by where the job takes you (sociologist Randall Collins calls these ‘pathways’ of individuation).i

The first rule of human geography is: follow the body. Setting off from Montreal he proceeds to a major airport in Africa, the Mideast or wherever is his goal. From there, by plane or other transport, he goes to smaller cities until he arrives at the last secure town in the region he wants to tour. This base serves as a jumping off point for his work. Chance and opportunity take him from there. Sometimes there is and sometimes not, a known destination. The means of travel are also ruled by happenstance and can include hitching rides with soldiers or other journalists. Such is the institutionalized routing for a restless, peripatetic, mobile photojournalist.

For Lemoyne, this is the arc of passage which takes him from the norms of peace to the inverted norms of contemporary war and its aftermath, which is his vocational terrain.

A far-off location and the regular change of location have also contributed to his formation. Even as the photographer enters the physical space of his subjects, he does not join them: he is in the crowd, but not of the crowd, he is not a member of the crowd’s society. He is of the crowd in his co-mingling and in sharing the same space, subject to the same physical conditions, the same weather. But he can always breakaway, remove himself from the crowd. What he can also do is disrupt his role as a photographer, to participate in the aid work of what he sees. Lemoyne has sometimes put down his camera to help dig latrines.

The itinerary is a world tour of misery: the Balkans, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Congo, Gaza, Afghanistan and, of course, Iraq. To these places Lemoyne brings his quiver of geo-political photographic styles: the immediacy of event-driven news-photos, the humanitarian aid photos (which are his mission work) and stand-alone photography for which there is no explicit client, except himself. Each aspect applies a different manner and approach, though he shifts between them fluidly.

Temporally, Lemoyne is concerned with that which is left after a battle – certainly the dead, but primarily the surviving war-affected, the remaining victims and the lives they must then struggle with – displaced, homeless, orphaned, injured, hungry, abused and discarded. He is the anatomist of a kind of corporeal and material post-traumatic stress. (Consider the dessicated snow-covered corpse found in 1996 in Bosnia-Hercegovina). As the statistics indicate, civilians and especially the young, are the principal casualties of present conflict. Between the combatants lie the victims who may not be partisans or belligerents but have prize value: the children can be dragooned into military service or slavery. Yet it’s not all hopeless, as he also sees how the children can “…heal, grow, learn, play and find joy under almost any circumstances.”ii Showing cattle grazing in Kosovo or amputee soccer in Sierra Leone, Lemoyne has a number of images here which testify to the resilience and adaptivity of both people and landscapes after their recovery from turmoil.

In an earlier essay I have written about what I called “photo-pragmatics”iii, which is that aspect of photography concerned not with what the photograph shows or says, but what it does, photography understood as a performative activity which has effect as well as meaning.

Among the things photographs can do is illustrate. Illustration is the visual support given to knowledge of another kind, usually verbal. The pictures serve to strengthen the idea. This may seem to make the imagery subservient, but it is not a trivial application, nor is the effect of illustration to be dismissed. Dorothea Lange worked with her second husband, economics professor Paul Taylor, to illustrate his economics text and the collaboration was fruitful.iv Illustration supports emotional energies. Among disciplines such as philosophy, cognitive psychology, intelligence studies and others, the emotions are currently enjoying an intellectual revival. These studies are redeeming the emotions from their status as embarrassing human baggage and are identifying them as the inevitable and necessary companion to reason in the formation of proper human judgement. It would appear that everything we need to know must also be felt.v

But if illustration is photography’s function to buttress what is already known, photography can also illuminate, which is to say, reveal new information and cast a light at dark corners. The pictures which emerged from the Abu Ghraib prison were graphic news and brought forward practices which had been hidden. Words had to catch up after them – the images were not subordinate – the texts which followed had to make sense of the pictures.

Illustration confirms the knowledge you already have, while illumination is a critical knowledge which forces an adjustment of what you already know. Both kinds of knowledge are necessary. As Lemoyne himself has pointed out, the photography of WWII was for morale building, while the imagery of the Vietnam war was to change people’s minds.

I have dwelt on this illustration/illumination distinction because I feel that Lemoyne’s work can be described in terms of their illustrative and illuminating functions. His almost exclusive use of a wide-angle lens provides a span of information. In their complexity, Lemoyne’s pictures show us what we might already know but then adds a complicating factor to the mix which undercuts our assumptions.

In a 2003 Iraq picture, a soldier is passing out a food packet to a child running beside his truck. We see the child and simultaneously the face of the soldier in the mirror. At first look it seems a heartening picture of a common sentiment. But it does not require a lot of research into the current Iraqui conflict to view it also as an example of a strategy of “combat marketing” which has made waging war and building peace so complex and contradictory. In this blurring of lines, the soldier brings both menace and food. With the militarization of aid, soldiers arrive as both a threatening and nourishing force. Humanitarian acts become war by other means. This does not soften the threat, but taints the food. The boys are also ambiguous: what are their intentions? Another photo from Iraq shows two dead civilians. Lemoyne has commented on them that it was uncertain if they were insurgents or innocent civilians. In an arena where things are not necessarily as they appear, visual information will be ambivalent or misleading. The killing of five volunteers from Medecins Sans Frontieres in Afghanistan was ascribed to just that confusion between military and humanitarian actors, a confusion intentionally fostered by coalition forces (in an effort to win support) and by the Taliban who claimed that MSF was working in the American interest.vi

Another image from Baghdad shows a Saddam statue with a Star of David drawn on his brow – a bit of anti-semitic nonsense commonly found in the region. But what, exactly, is the message? Was Saddam toppled by the Jews? Was Saddam an ally of the Jews? Or equivalent to the Jews? Is it an identifying emblem or a curse?

A picture from Palestine shows a crowd of enthusiastic youth – and is that a crushed bird in the boy’s hand? Two pictures from Kabul demonstrate a rich, cinematic span and the regularization, the normalization of violence. I would consider these pictures illuminating in that they provide corrective adjustments to our received ideas and complicate our attitudes about these regions.

As to his illustrative function, Lemoyne’s work with humanitarian organizations has produced graphic representations of dramatic changes to these bodies and how they function.

The literature is growing on the systemic and institutional failing of both the UN military and both UN and non-UN humanitarian interventions. Rule-bound and procedural, such organizations cannot combat ruthless, anarchic, lawless forces.vii The UN is designed to suppress conflict between states or at least between identifiable groups where there is a physical border (as in Cyprus), but incapable of dealing with conflict that is atmospheric: happening everywhere. The tendency is to attempt to limit predictable misbehaviour. The principle of non-intervention grants established states a free pass to oppress. As an officer of the UN peacekeeping force said, “We have orders to co-operate with the Rwanda authorities, not to shoot at them”. Asked if he could shoot at Rwandan authorities if they were killing innocent civilians, the officer replied, “Not even then. No”.viii For Lieutenant-General Roméo Dallaire, “Speed, innovation, imagination and understanding operational priorities were fundamental ingredients of success,” yet too often he got instead, “…rules, regulations and procedures that weren’t tied in any way to achieving our urgent aims.”ix One of the virtues of field operatives – be they soldier, aid worker or photographer – is the ability to identify the urgent.

The inability of aid organizations to do more than, “put Band-Aids on malignant tumours”x or, as was the case in Rwanda, for the UN forces to “be limited to a monitoring function”xi has caused the politicization of disaster relief and the development of humanitarian militancy. Médecins Sans Frontieres (whose slogan is “Soignez et témoignez” or “Care for and testify”) has abandoned its untenable neutrality and is now dedicated to rescuing and documenting on behalf of “humanitarian work which fights injustice and persecution”.xii

Certainly not alone, Lemoyne now marches under a flag which has not yet been designed. He is partisan on behalf of victims removed of their partisanship. Thrown off by the disaggregation of states, they are a third group created by the clash of the other antagonists. They constitute a humanity not defined by its national, political or ethnic identities. As Lemoyne himself describes it in his successful proposal for an Alexia Foundation grant:

“The overall aim of this project on war-affected children is to raise awareness of the nature of conflict in our time and of the international community’s obligation to intervene whenever and wherever human rights are violated. After WWII the international community created global structures to mediate between nations and governments, but not between ethnic groups or within borders. But as war changes, the international community must also change its ways of dealing with war.”

This is trans-national militant humanitarianism and is a challenge to the current way of administering the distribution of world pain. Policy is the application of theory and the material expression of power. Intellectuals (as the old definition goes, anyone who goes to work with a briefcase), speak the language of statistics and are the managers of power and policy. Among the unacknowledged duties of intellectuals is to determine who lives and who dies. This is clear in the instances of the judiciary and the military, but it also extends to the medical and engineering domains, to automobile and highway construction, equipment design, insurance, health policy and to anywhere in which general, statistically determined calculations determine group viability. They measure proportionality and necessity and perform a social “triage”, identifying those who will be cared for and those who will be abandoned. Photography shows us the faces of those chosen and we should be morally obliged to look at them.

During the Rwanda genocide, Dallaire recalls receiving, “…a shocking call from an American staffer, whose name I have long forgotten. He was engaged in some sort of planning exercise and wanted to know how many Rwandans had died, how many were refugees, and how many were internally displaced. He told me that his estimates indicated that it would take the deaths of 85,000 Rwandans to justify the risking of the life of one American soldier.”xiii Photographic witnessing, in its specificity and physical detail, challenges such rationing of life and questions this distribution of global distress.

Militant humanitarianism characterizes all forms of suffering and oppression as violations of human rights. This allows for the prosecution of tyrants and the call for humanitarian intervention. But as David Rieff reminds us, the real name for such intervention is ‘War’.xiv

Some have come to believe that, “Statistically speaking, news journalism is now the most dangerous profession in the world.”xv (Lemoyne thinks that firefighting probably is.) Historically, most journalists were killed inadvertently, the unintended fatalities of military operations. But increasingly journalists have become the explicit targets of force. This danger has made the job increasingly attractive to the young and adventurous, fed by the glamour and excitement of ‘extreme’ or ‘contact’ journalism and the immediacy of crisis imagery – any conflict will now draw hundreds of aspiring journalists. Young activists consider photojournalism as one way to express their social commitment. Such journalism resembles soldiering in its risk and zeal. Photographers enlist themselves to the cause. And the mortality factor adds to the work’s value.

Photographers have long lost their observer status. In the context of their implicit humanitarian partisanship, photographers will be treated as combatants without guns: part of the information arm of a global human rights movement. Tyrants will treat them as enemies. Authoritarian regimes don’t need a free press. Incidents like the arrest and death of Iranian-Canadian journalist Zahra Kazemi in Iran can be expected to occur more frequently. Such acts of oppression display a crude appreciation of what is at stake in global communication. After all, Kazemi’s purpose was not just to observe and report, but by that observing and reporting to change the Iranian regime. In some ways, activist journalists are not just calling for a free press, but for a press that is free to be effective, an instrument for human rights. Authoritarian regimes may view such activist photographers as pests, but more likely and more chillingly, as threats. Their response will not be pretty. Societies can permit a free press only to the extent that they legitimize opposition. In discussing the physical hazards of journalism, Lemoyne told me that he considered the bravest of journalists to be those who live in societies in which their work can be expected one day to draw the brutal attention of the authorities, and yet they continue to resist this coercive awareness.

The function of Lemoyne’s pictures is, yes, to make us more aware and mindful of human pain and to spur our moral energies. But also to show that things are not straightforward nor are the lines of demarcation clear. There are no sides except the side that finds the situation intolerable. Within this blur the struggles are both bloody and confusing. Perpetrators and victims often alternate. Yet the photographs also to serve to illustrate a reflexive examination of the workings of humanitarian endeavours. It is by his particular pathmaking that a unique set of encounters has occurred. One advantage of having these images in a book is that we can slow down our rate of apprehension, we can use them to think through to the world they open to us. Meditating on these pictures and the encounter each represents furthers our learning in navigating our New World Order and how it works and fails.

Notes

i. “Individuals are unique to just the extent that their pathways through interaction chains, their mix of situations across time, differ from other persons’ pathways.” Randall Collins, Interaction Ritual Chains, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004), p. 4.

ii. From Lemoyne’s Alexia Foundation grant proposal.

iii. Robert Graham, Undue Influence: Photography’s Powers, in the catalogue of Le Mois de la Photo à Montréal, 2001.

iv. “She and Taylor interviewed her subjects and combined words with photographs to create compelling social essays. The reports were designed to effect change, and they did: the government responded with money and programs.” Christopher Cox in Dorothea Lange, (New York: Aperture Master of Photography Series No. 5), p. 9.

v. In a review of a new book by the neuroscientist Antonio Damassio, Ian Hacking writes, “A continuing thesis of Damassio’s is that emotions are biologically necessary for making reasonable decisions: if a part of the brain needed for emotions is missing, decisions will not be reasonable.” in “Minding the Brain”, The New York Review of Books, June 24, 2004, p. 32.

vi. “Why we’re leaving Afghanistan”, by Tony Parmar, Globe and Mail, August 4, 2004, p. A12. Parmar is Director of Programs for MSF-Canada.

vii. For failure among the Blue Helmets see Linda Polman, We did Nothing: Why the Truth Doesn’t Always Come Out When the UN Goes In, tr. By Rob Bland, (London: Penguin Books, 2004) and of course, Lt. Gen. Roméo Dallaire, Shake Hands With the Devil: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda, (Toronto: Random House Canada, 2003). For the contradictions in humanitarian aid see David Rieff, A Bed for the Night: Humanitarianism in Crisis, (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2002) and David Kennedy, The Dark Sides of Virtue: Reassessing International Humanitarianism, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004).

viii. Polman, p. 209.

ix. Dallaire, pp. 491-492.

x. Rieff, p.307.

xi. Dallaire, p. 167.

xii. Rieff, p. 309.

xiii. Dallaire, p. 499.

xiv. Rieff, p. 341.

xv. Journalist Vaughan Smith quoted in “Where newshounds bond”, by Mary Ambrose in The Globe and Mail (Toronto), May 10, 2004, p. R3.