Reflections: Contemporary Art Since 1964 at the National Gallery of Canada (1984)

Graham, Robert. (1984). Reflections: Contemporary Art Since 1964 at the National Gallery of Canada. Parachute, 36, p. 65. Retrieved from https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3645266National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa May 11 – August 26

Moreover, I dot not feel compelled to hope for a more wonderful day before the fact in promo-proto-art history. I am not anxious to prefer to speculate against posterity. I like thinking here and now without sententious alibis…

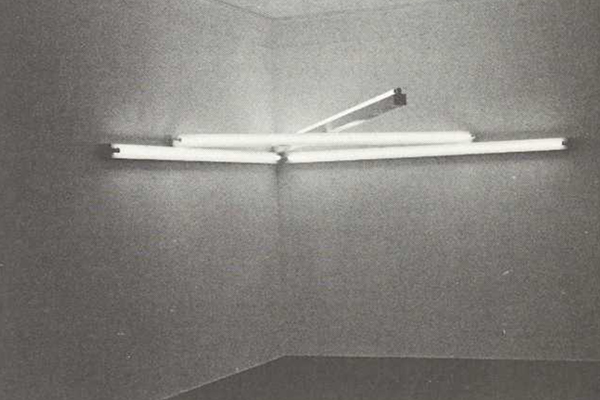

Dan Flavin 1

The exhibition of collections differs from other exhibitions in that rather than being organized by unities of origin — individuals, schools, periods, nations, etc. — a collection forms a group of works defined by their destination : the location of their arrival and reception. Collections of contemporary art differ, again, from those of past art by reason of the coextensivity of creation and receipt. In the special instance of commissioned work, the occasion of appearance and arrival is simultaneous. Clearly, the presence of the patron-collector, active or passive, contributes to the process of production, constitutes a factor of the environment and aids in drawing the work into being. “My consumers,” asked Joyce, “are they not also my producers?”

It has become customary to address this process of “teleological causality” with critiques of neglect, omis sion and suppression. As worthy as this approach is in correcting systematic oversights and identifying the unacknowledged biases of selection and gatekeeping, it rests ultimately on an appeal for addition or substi- tion to improve the canon, and fails to acknowledge the powerful ways in which institutions generate, transform and enhance objects and artifacts; that the regulation of art requires choosing, appropriating and adapting ; in short, the active construction of a culture. The manner in which works are absorbed by the appa ratus, serve to fulfill policy and are applied to various purposes, represents the positive participation of the institution in the culture it claims only to receive, en courage, preserve and reflect.

While, as everyone likes to repeat, the National Gallery has a long-standing tradition of involvement with living artists, the period in which these one hundred and thirty works were acquired marks a substantial change in the attitude of the Gallery toward contempo rary art.

First of all, this show would have been quite different had the Trustees not chosen, in the mid-sixties, to revoke a policy which prohibited the purchase of non- Canadian contemporary art. Art and culture (it was then understood) are phenomena of “sensual information” (the Baxters’ definition was current then) which are universal and transmissible; art was a global activity and the flow of information (aided by the technologies of communication) required free trade and the demolition of barriers. In 1967, the report of the Canada Council stated, “We feel that there is now a need for a well-directed exposure both in public and private galleries of our artists abroad, and for a concerted attack on the art markets of the world.”2 This mixture of technological utopianism and com mercial/cultural jingoism absorbed the earlier principles of modernity and transformed the avant-garde into a cadre of global champions for national prestige and an expanded market. Inviting Leo Castelli and his stable to the National Gallery was an expression of our confidence and willingness to play international hardball. The necessity for last year’s conference in Toronto, International Exposure for Canadian Artists, suggests that we are still trying to determine the rules of play.3

The enframing dimensions of time and history also underwent change. In her 1971 history of the National Gallery, Dr. Jean Boggs felt it necessary to defend the museum’s interest in contemporary art and to couch her apology in terms of its orientation as an historical museum : “We buy modern art in the hope — even on the gamble — that it will represent our time in the future.”4 Thus, the Gallery speculated in current work, on behalf of the future, to fulfill its mandate as a repository of the historical record. Eight years later, Boggs’ successor as Director, Hsio-Yen Shih, under lined the separate purpose of the contemporary art collection, “to exhibit the best and most imaginative creative artists of our time,”5 and “to contribute to Canada’s artistic vision and development by challenging the future in the perspective of the past, and revealing the significant perceptions of the present.”6 No longer modelled on the archive with its un assailable record, but on the laboratory with its end less experiments in perception, the institution of con temporary art comes to serve only the present, and what remains are the ephemera.

Probably the most indicative and successful (if not popular) moment during this period was when Brydon Smith introduced to the Gallery the work of the minimalists, and particularly the pieces by Dan Flavin. This fitting collaboration between artist and curator produced a show in 1969 which transformed the museum with its light. Displayed was an art stripped of reference and which, while produced for a specific location, defined its situation entirely formally. While offering an immediate experience, this work could only be understood as art through a detailed prepared knowledge.

Diana Nemiroff, the organizer of the exhibition, calls for a “process of endless self-correction.” This protean model of education demands that the lessons learned are to be successively discarded; the works are not so much re-examined as simply recognized and become mere illustrations of themselves and to kens in a fluctuating market. It is to the museum, that institution of collection and preservation, that we now go to learn how to unburden ourselves of the accumulated past.

ROBERT GRAHAM

NOTES

1. Quoted in Battcock, Gregory, (Ed.), Minimal Art, (New York : Dutton, 1968), p. 402.

2. 10th Annual Report of the Canada Council 1966-67, (Ottawa : Canada Council, 1967), p. 17.

3. See Johanne Lamoureux’s review of the conference in Parachute, 32, Fall 1983, pp. 46-48.

4. Boggs, Jean S., National Gallery of Canada, (Toronto : Ox ford Press, 1971), p. 62.

5. Annual Bulletin of the National Gallery of Canada 1977-78, (Ottawa, 1979). p. 12.

6. Ibid, p. 14.