Points of View: Photographs of Architecture (1981)

Graham, Robert. (1981). Points of View: Photographs of Architecture. Parachute, 23, pp. 39-40. Retrieved from https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3645253The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts January 16 — February 15, 1981

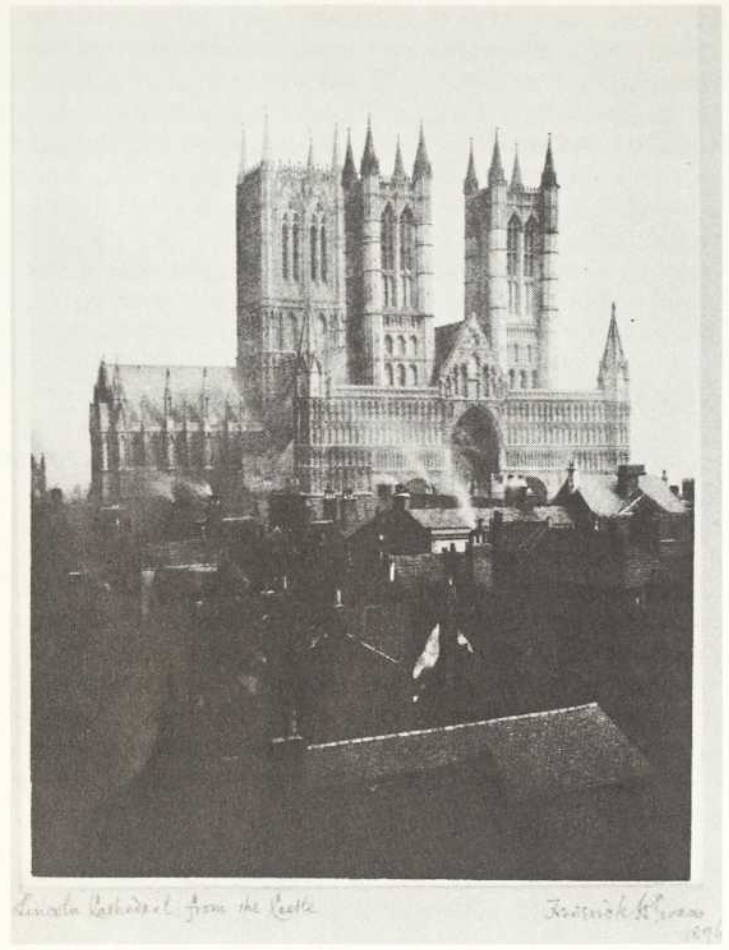

The title of this exhibition is misleading, for there is really only one point of view presented here and that is the perspective of Photography. Two hundred samples of a century and a half of architectural photography, drawn principally from the collection of the National Gallery of Canada, were gathered together and divided into five categories: the single monument, the single monument in urban contexts, interiors, façades and building details. The complex historical interaction between photography and architectural practice is reduced to the still moment of photographic exposure. The fastidious details of photo-historical connoisseurship which accompanied the images provided the signs of scholarship, but it is an exhibition of little thought.

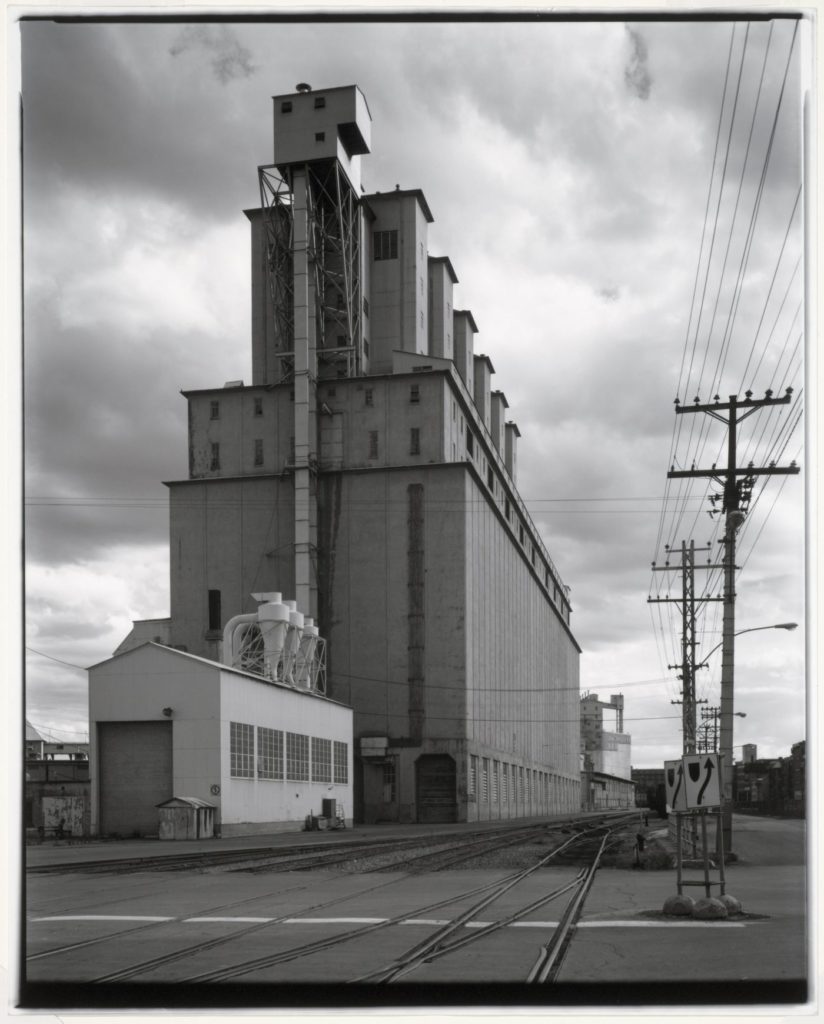

During the run of the show David Miller, one of the photographers represented, prefaced a discussion of a study he did of a Montreal harbour grain elevator with the question, “How does one photograph an architecture which has no style?” Architectural style is a code; to build is to enact a code which establishes the rules, procedures and expectations of a building’s measure. As such there is never a building without “style” or an architecture without a code. These codes are established, transmitted and transformed. Shifting codes constitute architectural change. Photography has its role in architectural code formation, but this role is not determined exclusively by the photographer.

Le Corbusier included in his 1923 treatise Vers Une Architecture photographs of Canadian and American grain elevators. For him these structures argued for the harmony and purity of the Engineer’s aesthetic which Le Corbusier wished to propose for the agenda of a new architecture. Fifty years later, Venturi, Brown and Izenour in their book Learning from Las Vegas reproduced one of the grain elevator illustrations from Vers Une Architecture. Only now the same structure comes to plead for a richly associational, highly symbolic industrial vernacular.

My point is that detailed research of a photograph’s origins, which is the methodology of curators, can only rarely illuminate the active interrelationship between a photograph and its function in meaning formation. Quietistic surveys suppress the more dynamic history of the medium and its application as a device of rhetoric and argument within fields such as architecture.

Le Corbusier ends Vers Une Architecture with a picture of a briar pipe. For the reader this ultimate image poses an architectural question, it is a photograph of architecture. The “point of view” of this exhibition can not include any such idea.

ROBERT GRAHAM