Photographies en Couleur / Colour Works (1980)

Graham, Robert. (1980). Photographies en Couleur / Colour Works. Parachute, 18, pp. 48-49. Retrieved from https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3645247Yajima/Galerie, Montreal, 7 February — 1 March, 1980

Photo-works by lain Baxter, Benno Friedman, Charles Gagnon, John Pfahl, Gabor Szilasi, Serge Tousignant, Christian Vogt.

Compared to the great 19th century salons and academy shows, with acres of paintings hung edge-to- edge and from floor to ceiling, contemporary group shows resemble several one-man shows sharing a room. The works of the single artist are grouped together and then each artist is separated from the others by wide margins of white wall or doorways. Each figure is granted a local domain of attention and protected from noisy neighbours. Organized this way there is a tendency to view the works monologically; we are encouraged to forget that when artists speak, they are usually speaking to each other.

John Pfahl is a photographer who tampers with manifest landscape by adding string or other foreign objects to the scene to emphasize the shapes of ter- rain, surface, or horizon. These supplementary props act as markers for the eye to focus on some specialized feature of the picture.

Pfahl’s photography is the transformation of nature into a still theatre of whimsical artifice. The ten photos shown here, taken between 1975 and 1977, display his playfulness with language, image and contour, but fail as an examination of unreflected vision—they fail because the technique of adding foreign items to our view could lead to an alienated vision which was aware of the habits of seeing. Instead of a possibly Brechtian image with its capacity to irritate the eye so as to call attention to the act of looking, we have moderately wry illustrations of incongruity and disjunction.

Benno Friedman is represented by three pieces from the mid-seventies. He also transforms his landscapes, but after the exposure has been taken by tinting and drawing on the photo with pencil or water colour. What these additions perform is a reading of the look of nature as delivered by the indiscriminate lens. Friedman accentuates a line, points out a feature with colour and establishes a shift of foci from the original photograph and its hierarchy of interest points. For Friedman photography would seem to be a means to i drawing — the beginning of a return to something like draughtsmanship. While the relationship between drawing and photography has been often expressed in this century (‘drawing with light’, etc.), the issue is usually expressed in terms of their similarity and of the support each can provide for the other. What is curious about Friedman’s work, such as Topology (1976), is the manner in which his modifications struggle against the neutrality of the base photograph. Friedman, I suggest, has some conflict with photography and displays a distrust of that too often complacent medium.

Gabor Szilasi betrays no such doubt and his four roomscapes are the most transparent and unreflective use of the camera in this exhibition. Umberto Eco once wrote a description of kitsch as “that work which, in order to justify its function of stimulating effects, struts about in the borrowed plumes of other experiences Szilasi presents, in a deadpan manner, the flawed interiors of the kitsch culture —the Elvis Presley painted plaster bust, the barber shop with all its bric-a-brac and other scenes rom the low-taste life. Kitsch has been a trite issue in the art world for some time now and has been the source of a lot of campy fun, but Szilasi’s mediations perform a disagreeable trick — he brings the banal back alive and makes it fit for art. He coolly reproduces he gaudy colouring and ersatz aesthetic for our amusement while keeping the distance between the worlds of the viewer and the viewed nicely apart. Following Eco’s definition, Szilasi’s photos can be seen as kitsch themselves — the kitsch of the gallery-goer with its patronishing irony and his eye for the exotic. Szilasi is one of that specie of photographic researcher who seeks out the freaks of culture to put on show for our own conceit.

There are two photos from Christian Vogt and they are fine, crisp and sure. The 1978 untitled cibachrome of marble steps front lit by flash, at what seems to be dusk, is a keen study of architecture and atmosphere by an attentive and careful sensibility.

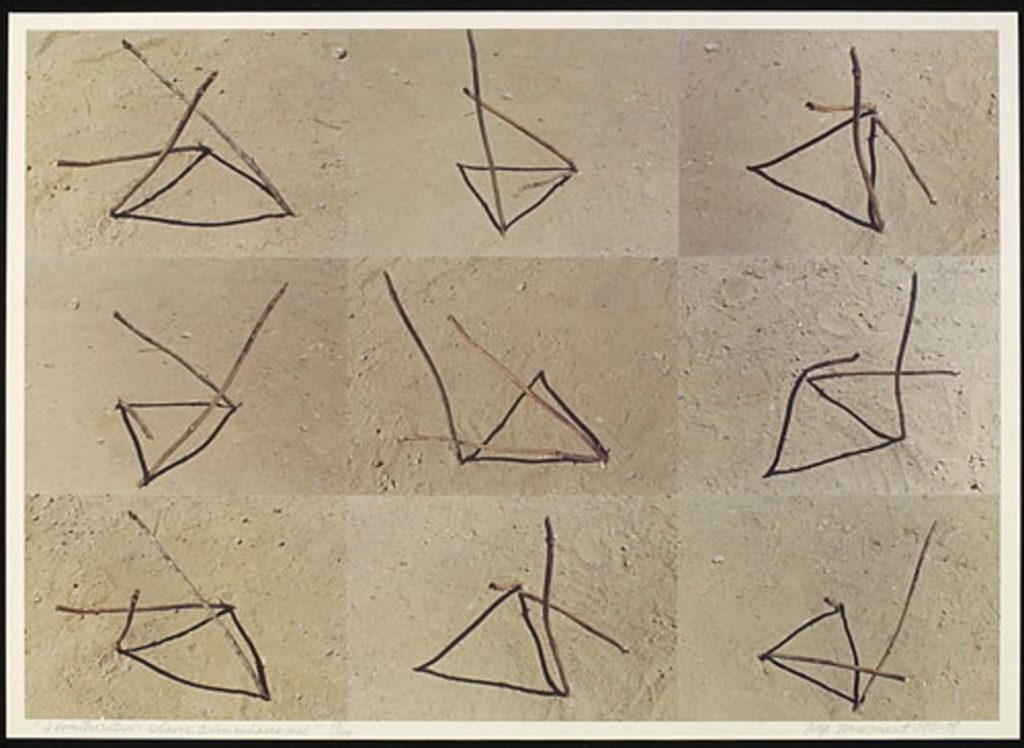

Serge Tousignant continues his investigation of perception with six photographic diptychs called géometrisation solaire triangulaire. Each piece is a pair of photographs, attached side by side, of three short sticks stuck in sand on a sunny day. The three sticks cast shadow lines which form a triangle on the ground. Each of the pair of images has exactly the same triangle of shadow lines as the other, but there is one difference in position of one of the member twigs. Thus, for example, the left hand image of one diptych will have a stick at each apex, placed at such an angle so that the shadows formed by the sticks make a triangle. The right hand image will have the same triangle, only, one of the sticks has been moved to share a corner with another. It is placed at the necessary angle to duplicate the original line of cast shadow.

Tousignant’s playing with cause and effect in this manner is part of his continuing research into the modes of light and dark, scale, perspective and size, which are the basis of our capacity for visual representation. The problem with the form of his investigation so far, is his practice of placing a known or announced fact behind his presented illusion. In this work the ‘fact’ (the sticks and their arrangement) are presented simultaneously with the ‘illusion’ of shadow lines. In other words, he would seem to be suggesting not that the camera lies, but that the camera (or viewer) is cheated of what is really there. Thus Tousignant becomes a sort of positivist who is forever seeking the objective state behind the subjective perception, and who performs a critique of perception by means of showing the power of deception. Tousignant begins by measuring the distance between representation and thing, instead of noting that distance is and always has been there, and yet still we have the capability to know and to represent.

lain Baxter’s artistic entrepreneurship was a refreshing alternative to the usual humanistic homilies against commerce, but it may have proven that the risks he took with his integrity were too great. These nine pieces, most of them completed this year, are all composed of SX-70 photos attached to sheets of drawing paper with supplementary drawing ex- tending from or passing through the polaroids. One of the pieces, An approximately 10” red casually painted square, has the photo of a hand with paintbrush in one corner of the red square with paint overlapping onto the photo. The title hints of one characteristic of this collection — the casualness, even the hastiness with which they seem to have been assembled. There is the smell of corruption here; not the ordinary decay of old fat artists, but the corruption of discrimination which permits an artist to send out undistinguished, careless and unexamined work. Seven lines drawn with Blue Jiffy Marker — King Size displays Baxter’s sensitivity toward brand names and his insensitivity toward his own work — there are eight lines drawn. Baxter might well be the first of a new art type — the avant-garde hack.

John Cage once described the different types of performers in terms of the function of the photographer who can approach his task in several ways. One of the ways was to enter “the deep sleep of Indian mental practice — the Ground of Meister Eckhart identifying there with no matter what eventuality.”2 This is a clear definition of the operations of Charles Gagnon’s passive eye and carefree finger as demonstrated in these SX-70 landscapes. All were shot through a win- dow and during winter over the last three years and they are precious samples of that indifference to even- tuality which Gagnon’s art entails. “Art”, Gagnon has said, “is not communication, but communion.” Although some of the photos seem to have been taken on the same occasion, and are gathered together in a group, they do not display the character of seriality—there is nothing gained by their com- parison. Each is a meditative moment based on that study of faith, which Gagnon shares with other artists of the last thirty years, which directed that the properly trained and disinterested hand would allow the aper- ture to become an entranceway for nature. These photos are taken in the hope of a revelation, and it is only fitting that they should be so murky and visually ambiguous. It is not Gagnon who is being difficult, but that which he hopes to bring forth.

ROBERT GRAHAM

NOTES

1 Eco, Umberto. The Structure of Bad Taste (1964), Translation in Italian Writing Today, ed. Raleigh Trevelyan, Penguin Books, Baltimore, 1967. p. 121.

2. Cage, John. Silence MIT Press, Cambridge, 1966, pp. 36-7.