Donigan Cumming: undoing documentary (1984)

Graham, Robert. (1984). Donigan Cumming: undoing documentary. Parachute, 34, pp. 19-24. Retrieved from https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3645264I must confess no object ever disgusted me so much as the sight of her monstrous breast, which I cannot tell what to compare with, so as to give the curious reader an idea of its bulk, shape and colour. It stood prominent six foot, and could not be less than sixteen in circumference. The nipple was about half the bigness of my head, and the hue both of that and the dug so varified with spots, pimples and freckles, that nothing could appear more nauseous: for I had a near sight of her, she sitting down the more conveniently to give suck, and I standing on the table. This made me reflect upon the fair skins of our English ladies, who appear so beautiful to us, only be cause they are of our own size, and their defects not to be seen but through a magnifying glass, where we find by experiment that the smoothest and whitest skins look rough and coarse, and ill coloured.

Jonathan Swift 1

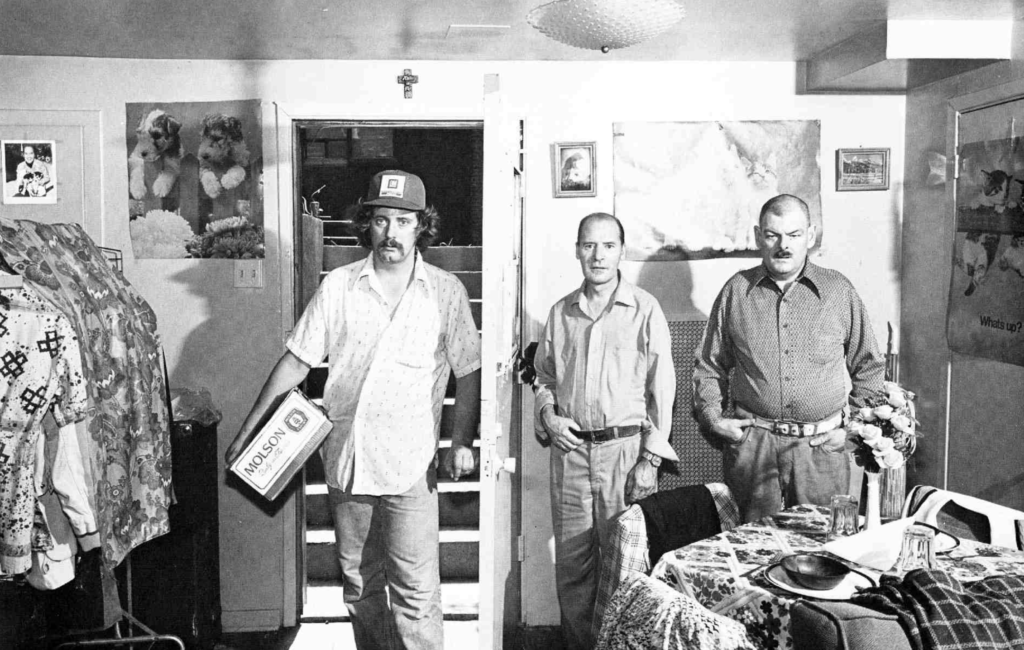

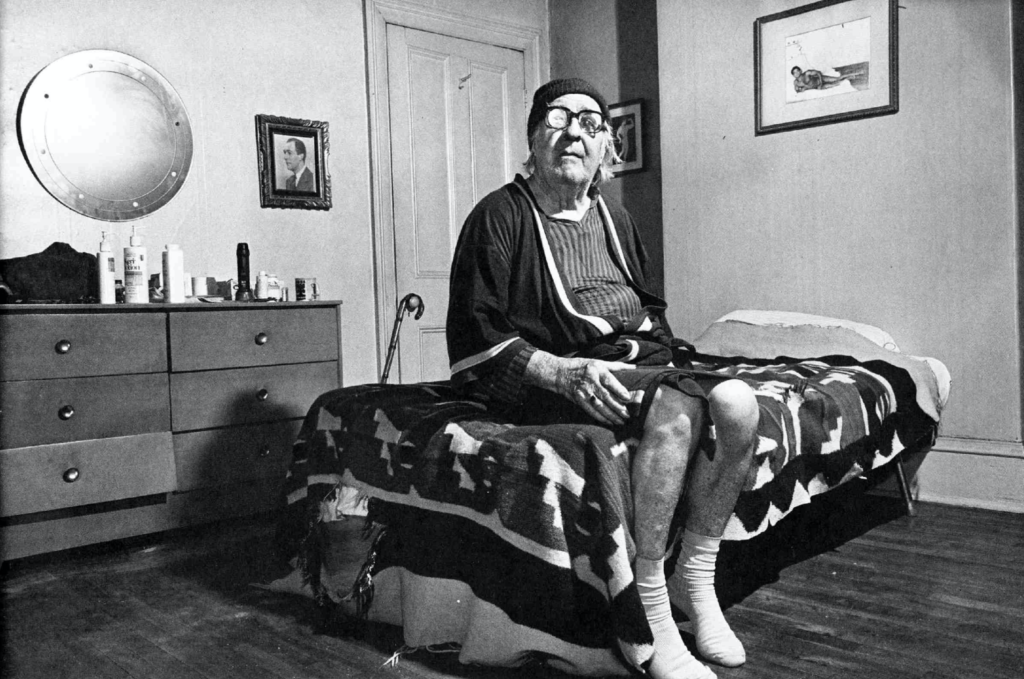

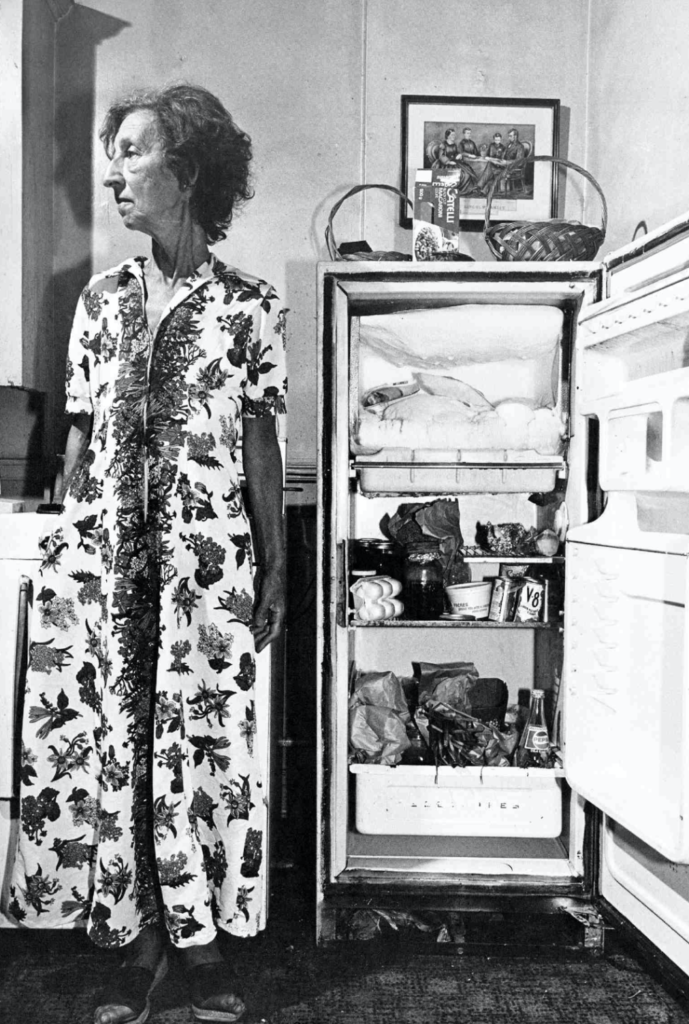

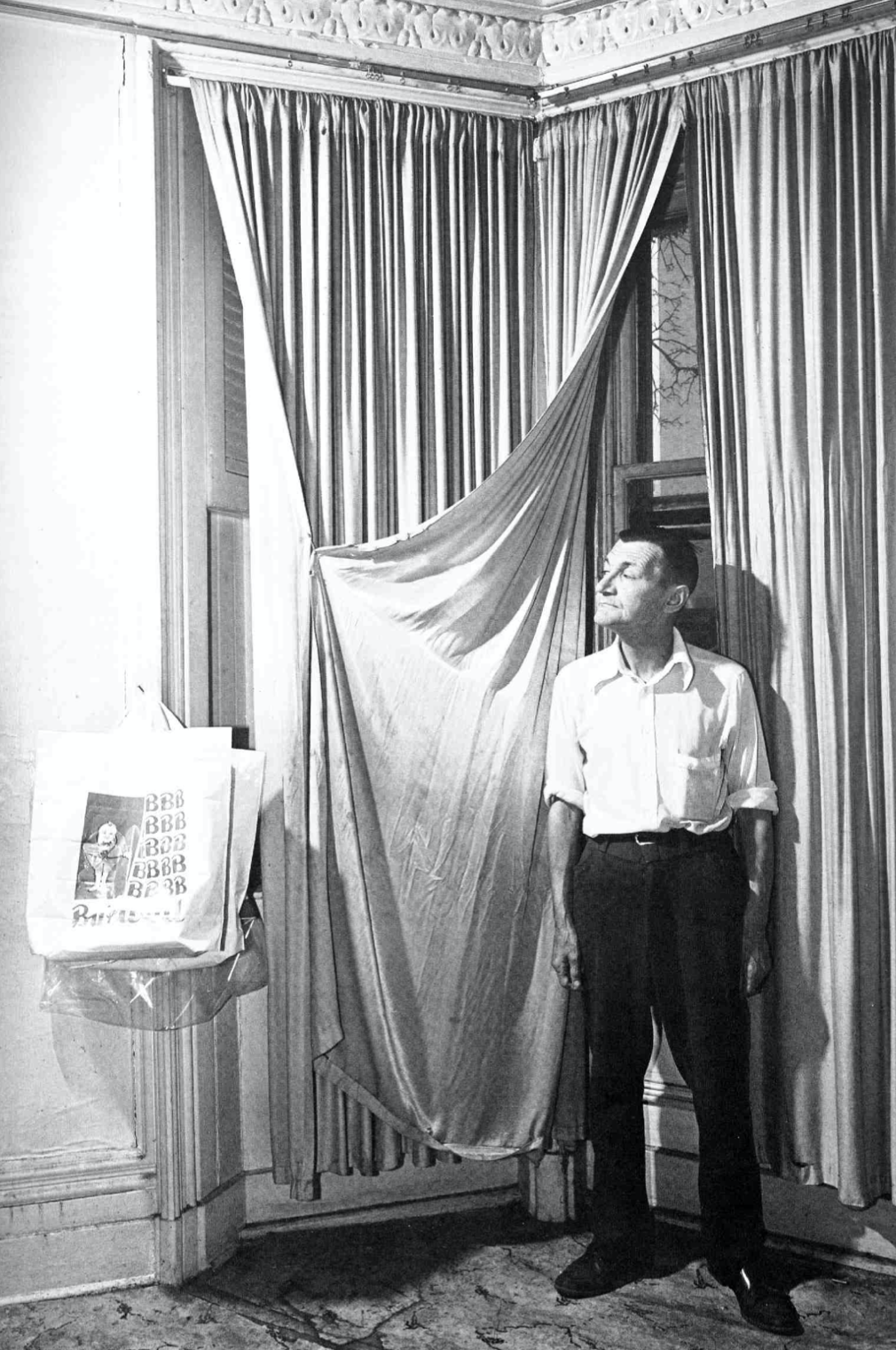

The project began when Donigan Cumming asked at the local grocery store if he could accompany the delivery boys as they delivered their beer and groceries. (In display, the first image is usually of the empty storeroom with the sections marked off for inventory.) Together, they arrived at the customer’s home, where the photographer met the occupants and made a proposal: he wished to photograph them and offered, in return, to provide a selection of “technically proficient snapshots” for them to keep. There was some discussion, and about half of those approached agreed. Appointments were established and the sessions began.

While shooting, the photographer asked his subjects to act and to pose in various ways, to hold sundry objects or documents found around the home, to stand beside the refrigerator with the door held open, to shut their eyes (the mother, in her enthusiasm, covered the baby’s face with her hand). When finished, Cumming provided the prints, obtained releases (standard for models) and paid a fee in consideration.

Like a good sociologist, the photographer had prepared a field to investigate — the sort of group which might interest a social agency studying dietary habits or a brewery doing sales research. Yet instead of attempting to record what he found, as he found it, the photographer deliberately sought, and got, his subjects’ compliance to collaborate on a project of artifice and dissimulation; to present themselves and their surroundings in ways that they would not them selves have chosen; to become actors in a theatrical production, and all this for some unstated purpose.

While evidently done with the subjects’ agreement and cooperation, the project was not produced as the joint effort of a community and a photographer, but as the result of a contract. Contract is the opposite of unity, for a contract does not diminish the difference between par ties, but recognizes and fortifies the difference while permitting a concerted action. Each side in a contract retains its identity and seeks to protect its own interests, while providing mutual exchange and fulfilling the terms of the agreement.

All of this makes many viewers terribly uneasy: we are troubled by the seeming lack of delicacy or consideration shown by the photographer in his treatment of these people, and we fear that they have been manipulated into presenting themselves in ways unnatural and arbitrary. The aggressive illumination and staging scrutinizes the figures and their surroundings. If traditional documentary displayed unrecognized heroes, here there is an inversion to mock heroics and we experience a chill of embarrassment at the perceived threat to dignity. We become mis trustful of the information and suspicious of the intent. The situations are not identified, the individual photographs are untitled and the name of the series itself is elusive: Reality and Motive in Documentary Photography.

THE OFFICE OF DOCUMENTARY

Sometimes I think Challenge for Change is a devious plot to make poets think like bureaucrats.

N.F.B. worker 2

A crucial component of the heritage of documentary photography is the role it was assigned in cultivating socioeconomic knowledge, both as a tool of research and investigation, and as a means of creating public awareness of the knowledge produced. Because of its ability to render the particular and the material, photography was called upon to flesh out economic readings and to offer its interpretative and illustrative powers to the issues raised by the findings of demographic and statistical analysis. Photography was identified as useful in fortifying, and making accessible, arguments and appeals in public debate. Photographic images provided emotional content in the struggle for social change.

The story of Dorothea Lange’s work with the economist Paul Taylor, during the Thirties, displays some of the elements of this dynamic interaction. Taylor was commissioned by the State of California to examine the problem of migrant labor. He insisted on having a photographer as a research assistant. Lange’s photographs of the shanty towns that had appeared and the dis tress of the unemployed, were included in Taylor’s subsequent report. It has been acknowledged that the photos were instrumental in moving the government to act and, later, in providing public justification of the programs that resulted. Documentary photography became recognized for its ability to help persuade both legislators and constituents in matters of public policy.

The U.S. government sought to adopt this capacity in the formation of the photographic division of the Farm Security Administration, un der the direction of Roy Stryker.

Stryker, a primitive ethnographer, once suggested that the photographers should attempt to show the “relationship between density of population and income of such things as: pressed clothes; polished shoes and so on… the wall decorations in homes as an index to the differ ent income groups and their reactions.”3 Among his favourite photographers was Russell Lee, of whom he once spoke: “When his photographs would come in, I always felt that Russell was say ing, ‘Now here is a fellow who is having a hard time but with a little help he’s going to be all right.’”4 One could hardly wish for a more succinct summary of the hopes and limitations of New Deal policies of economic intervention than that.

In Canada, the history was somewhat different. The National Film Board’s early development coincided with the mass mobilization of the Second World War. As a government agency, with a national purpose, the Board was expected to provide the country with instructive and in spiring films as its contribution to the war effort.

After the war, the N.F.B. continued to supply the government and its departments, the various film products and services that a national administration had become dependent upon. Yet the Board was also granted a certain autonomy in deciding how it should direct its activities. This license was given not only because the government feared charges of censorship, but also because the principals involved recognized that the making of films, even documentary films, required free development and could not be directed by a centralized authority. John Grierson’s definition of documentary as the “creative treatment of actuality” stressed the making, rather than the matching, of reality as the documentarian’s task. The ensuing history of the Board’s investigations and experimentations serves as an exegesis of that original description.

This is none more evident than in the program, begun in 1967, called Challenge for Change. With a mandate to develop “film activities among the poor,” the filmmakers set out to make films which reflected radical changes in the relationship between filmmaker, subject, and viewer, and all to the benefit of the disadvantaged.

The program involved a wide variety of experimental efforts, but two productions (one a success and the other a failure), are worth mentioning.

The residents of the Fogo Islands, off the coast of Newfoundland, were threatened with a government relocation program. The N.F.B. crew produced a film, under the control of the islanders, which, when shown to the authorities, persuaded them to abandon their plan. “We finally had fishermen talking to cabinet ministers,” exulted one filmmaker.5 In providing a contemporary mode for peripheral citizens to petition centralized authority, the program proved effective.

The Things I Cannot Change showed the dispiriting condition of a Montreal family with ten children and the father unemployed. “After the film appeared on television, the family suffered the ridicule of their neighbours. They were hurt by the film, not helped.”6 In their rush to portray the neglected, the filmmakers exposed only the hopelessness, and produced not recognition and relief, but shame instead.

The program revealed that to the extent that filmmakers suppressed their participation in the production of films, on behalf of, and in deference to, the community to be represented, they permitted a result which repeated and re produced the boredom and self-delusions the community was experiencing in the first place. The filming became mired in the stuck patterns and habits of thought, and in the internal di visions and conflicts of the participants. Trusting that unfettered truth would simply pour into their cameras and microphones, the filmmakers dis covered that more likely it would need to be found imaginatively and creatively, if approached with stealth, obliquely.

ILLUSIONS AND COUNTER-ILLUSIONS

It is full of improbable lies, and for my part, I hardly believe a word of it.

An Irish bishop on the publication of Gulliver’s Travels

Bound so closely with the obligations of providing evidence and pursuing controversial pur pose, documentary photography has always been subject to questioning of its authenticity. The history shows a constant shifting and modifying in the creative strategies of documentary producers, in an effort to offset (or hasten) the decay of credibility in conventional practices.

Dorothea Lange could say, “First — hands off! Whatever I photograph I do not molest or tamper with or arrange,”6 and we would believe her to be sincere, but only because she places the emphasis on that which is photographed. We have since learned that her manipulation of the images in their selection and cropping was quite active and determined. 7

Walter Benjamin wrote of August Sander:

Shifts in power, to which we are now accustomed, make the training and sharpening of a physiognomic awareness into a vital necessity. Whether one is of the right or the left, one will have to get used to being seen in terms of one’s provenance. And in turn, one will see others in this way too. Sander’s work is more than a picture-book, it is an atlas of instruction. 8

Here is Benjamin showing his magic materialism and his most idiosyncratic political naturalism. Such an “atlas of instruction” would require the most steady, ancient, and consistent of states to be reliable. Today the notion is risible. Not only are our origins invisible, our appearance hardly testifies to our present position.9

DOCUMENTARY KNOWLEDGE

In bringing up the issues that I have, to the extent necessary, I hope to have established a sense of the historical field in which Cumming’s work operates with such tension. Tension itself, as experienced in that initial unease, also matters. We are fascinated by an imagery which, in a hazardous formula, seems both powerful and flawed. In contrast to the fastidious care taken by serious documentarians to limit the effect of their influence, Cumming negotiates a contract. Against the fear of intervention, he tips his hand with every image. In Lange’s terms, he has tampered with the relationship, molested the situation and runs the risk of producing a result socially opprobrious and pornographic.

When we seek to locate the region of these transgressions, the sites of boundary violations, we find a very specialized set of rules of photo graphic conduct, designed to satisfy the criteria for legitimizing and organizing a range of purposive tasks. What I wish to suggest is that the emphasis, in the documentary tradition, of fulfilling the requirements of its office, necessitates the formulation of a detailed protocol in the production of social documentation.

Cumming, while appearing to operate within the realm of bureaucratic documentary (in that his work resembles the traditional, useful examinations, and investigations of social phenomena), deviates from the norms of production and mixes a blend of codes (from the realms of fashion, commerce, etc.) to bring into relief the developed operating principles of the tradition. Against bureaucratic earnestness, Cumming offers an internal critique, subversive and playful in its refusal to respect the assigned duties of documentary.

That we view and experience each other socially is a condition of being human. That we view and experience each other sociologically is quite an other matter. Sociology, as a discipline, and the many sociological theories that have emerged, are bound to an historically developed consciousness. The transmission of social scientific knowledge is not limited to its formal study, but extends into our work, our journalism, and even our personal communication. While the range of social scientific awareness runs from the sophisticated to the folk, the effect of its assumptions is pervasive. We have all absorbed and internalized, to varying degrees, the descriptive and taxonomic tools of sociological inquiry. The sense of a society which reaches far beyond the immediate, local, and familiar, requires the heuristic devices of classification, categorization typification, etc., to permit us to manage our experience. As such, this learned awareness occupies a powerful mediating position in our social relations.

The authenticity we acknowledge in a documentary photograph is an individual and collective construct. We judge the images according to their fittingness with projected reality. All successful documentary practice must satisfy the conditions of an accepted theory. The theory is not a theory of documentary, or photography, or even perception, but a theory of socioeconomic reality which, in turn, serves to enframe and support the documentary statement.

Controversies over documentary veracity which argue around issues of perceptual trickery and informational fraud or the biases and prejudices of the photographer (I can tell you now — you will always find some), are misguided and an un necessary distraction.

The truth of documentary is always an historical truth and is based on a present, residual or emerging pattern of social perception. The historical truth of Dorothea Lange’s New Deal revelations or August Sander’s physiognomies remains unassailable. The effort of the Challenge for Change group to realize a vital regionalism and de-centralization is not made false by ensuing events. That we cannot continue to work in their ways does not diminish their truth.

In its alliance with social scientific knowledge, documentary has proven itself effective in providing communication between groups and entities who have focussed interests and formed a self-typifying unit (“Fishermen talking to cabinet ministers”), and, generally, in presenting socio economic manqua socioeconomic man. Therein lies its limitation : the inability to demon strate realities, concerns, and relationships be yond the ken of mediating social knowledge. The disenchantment with documentary is as much a disenchantment with such mediations.

“It was only after viewing Donigan Cumming’s work that my whole concept of documentary photography was challenged,”10 wrote David Barbour (once of the N.F.B.). Cumming’s work appeals to encounters outside of documentary’s usual channels. Paul Ricoeur, in a 1954 essay, called this alternative, the phenomenon of the “neighbor.”

The neighbor is characterized by the personal manner in which he encounters another indepen dently of social mediation. The meaning of the encounter does not come from any criterion immanent to history. 11

While Ricoeur did not wish to abandon or refute mediating social knowledge, he spoke for the recognition of its limits and that a portion of consciousness be permitted an alternative.

The theme of the neighbor rather condemns a vertical extravagance, that is, the tendency of social organisms to absorb and exhaust at their particular level the whole problematic of human relationships. 12

Is this a clue to the sense of Robert Frank’s exiling himself from documentary, to go to Nova Scotia and take snapshots of his friends?

Cumming’s work, with its fulsome, noisy, and conflicting evidence, exhausts our capacity to render the usual readings we have become pre disposed to. If documentary demonstrated a victimology of production and consumption, the photography ‘of the neighbor’ shows, in Ricoeur’s words, the “theology of charity” which is posited as the necessary adjunct to any social relief from the frustrations of contemporary existence.

In citing Swiftiana, I have done so only partially because of the parallels: the distorting effect of magnification and close detail; Swift’s satirization of a ‘documentary’ form, the travel journal ; and the comic irrelevancy of the work’s verisimilitude. There is also, in Cumming, a touch of the Dean’s dark misanthropy: here is no humanist, as he is sometimes described, but a counter humanist, who, nevertheless and ironically, indicates for us the possibility of a redeemed documentary “of the neighbor.”

NOTES

1. Swift, Jonathan, Gulliver’s Travels, (Harmondsworth : Penguin, 1967), p. 130.

2. Jones, D.B., Movies and Memoranda, (Ottawa: Deneau, 1981), p. 167.

3. Quoted in Tagg, John, “The Currency of the Photograph,” in Thinking Photography, ed. Victor Burgin (London: Macmillan, 1982), p. 126.

4. Ibid.

5. Jones, p. 163.

6. Quoted in Masters of Photography, ed. Beaumont and Nancy Newhall, (New York : Park Lane, 1958), p. 140.

7. Brumfield, John, “How Some Men May Be Seen To Walk On Water,” Afterimage, Vol. 10, No. 7, Feb. 1983 (Rochester).

8. Benjamin, Walter, “A Short History of Photography,” Screen, Vol. 13, No. 1, Spring 1972, (London).

9. A reporter at a Montreal hockey game saw a fellow hang ing around the pressbox and asked a guard, “who this impudent guy was, acting as if he owned the place. The guard informed the embarrassed commentator that his visitor had been Peter Bronfman and that he did, in fact, own both the place and the team.” Newman, Peter, Bronfman Dynasty, (Toronto: Seal, 1979), p. 279.

10. Barbour, David. Program introduction, Document, The Photo Gallery, Ottawa, April 14 — June 19,1983.

11. Ricoeur, Paul, “The Socius and the Neighbor,” in History and Truth, (Evanston: Northwestern, 1965), p. 109. 12. Ibid., p. 107.

Les stratégies contre-documentaires du travail de Donigan Cumming (un photographe de Floride, habitant maintenant Montréal) conduisent à remettre en question le lien que la photographie documentaire entretient traditionnellement avec la science sociale, lien qui a bloqué les capacités du documentaire à montrer des aspects de la réalité au-delà des rapports visibles de production et de consommation.

Le travail de Donigan Cumming permet de mettre en évidence le pouvoir et les effets de cette tradition, en même temps qu’il indique une conception différente du documentaire pour la description de laquelle on peut faire appel aux notions de “théologie de la charité” et de “voisin”, proposées par Paul Ricoeur.

Robert Graham is an art critic living in Montreal.