Contemporary Canadian Photography (1986)

Graham, Robert. (1986). Contemporary Canadian Photography. Parachute, 42, pp. 39-40. Retrieved from https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3645272National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa November 1 — December 29

As is now well known, when the Canadian government originally announced its intention to abandon and effectively destroy the activities and collection of the Stills division of the National Film Board, the ensuing protest of the photographic community was sufficient to cause the authorities to reconsider. The result was the establishment of a new organization, the Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography as one of the National Museums of Canada, to house and maintain the Board’s collection and to acquire and promote new photography.

While the founding of the C.M.C.P. serves to preserve much of the N.F.B. material, it nonetheless marks, as the new Chief Curator Martha Langford put it, that, “For still photography at least, Grierspn’s Canadian experiment has reached an end.”

And it was doubly experimental: innovative in its attempt to establish a quasi-autonomous governmental photographic service, it also based its activities more on the research model of a laboratory than the curating tradition of a museum. Determined by a structure of command, the photographic projects were formed as investigations and applications of explicit social policies. As such, results were measured above all by their satisfaction of assigned tasks. The actual photographic documents that accumulated over time were considered an incidental by-product of the process. The resulting “collection” took on an importance more valued, it would appear, by those outside than inside the Board. Both the 1951 Massey and 1982 “Applebert” Commissions considered the Board as both research institution and repository. Massey called the collection “an historical record,” while “Applebert” recommended its preservation on the grounds of photography’s status as an art form. For a John Grierson, neither of these were particularly compelling concerns: the value of photography was as an instrument to be applied toward specific, usually educative, goals. The form of that instrument was, of course, primarily the documentary.

And that, as Penny Cousineau remarked upon in a symposium held at the Gallery, brings up the other turning point of the exhibition: does the show represent the end of that kind of documentary photography for which Canada was renowned? As presented in the exhibition, the chronology of the collection begins to display, in the early seventies, a divergence from documentary purity toward an expansive pluralism. From then on are included narrative, pictorialist, expressive, imaginative, constructive works more concerned with issues of photography or perception than society. In this context, the introduction of colour in works which might otherwise be considered documentary seems to preclude them from that category, as if colour itself was ineligible information — extraneous to documentary’s purpose. And to underscore this shift, the last picture in the accompanying book is like an exclamation mark — a bold purple Evergon Polaroid self-portrait Mask and Pineapple (1984) — not the kind of picture that would have ever been found in Grierson’s National Film Board.

The C.M.C.P. is a new institution with a new identity, yet it appears with the legacy of a powerful heritage. What is interesting is that in struggling with its tradition it will provide a unique way of defining the photographic debate. With all this talk of ends, we may fail to notice there’s been a beginning.

ROBERT GRAHAM

NOTE

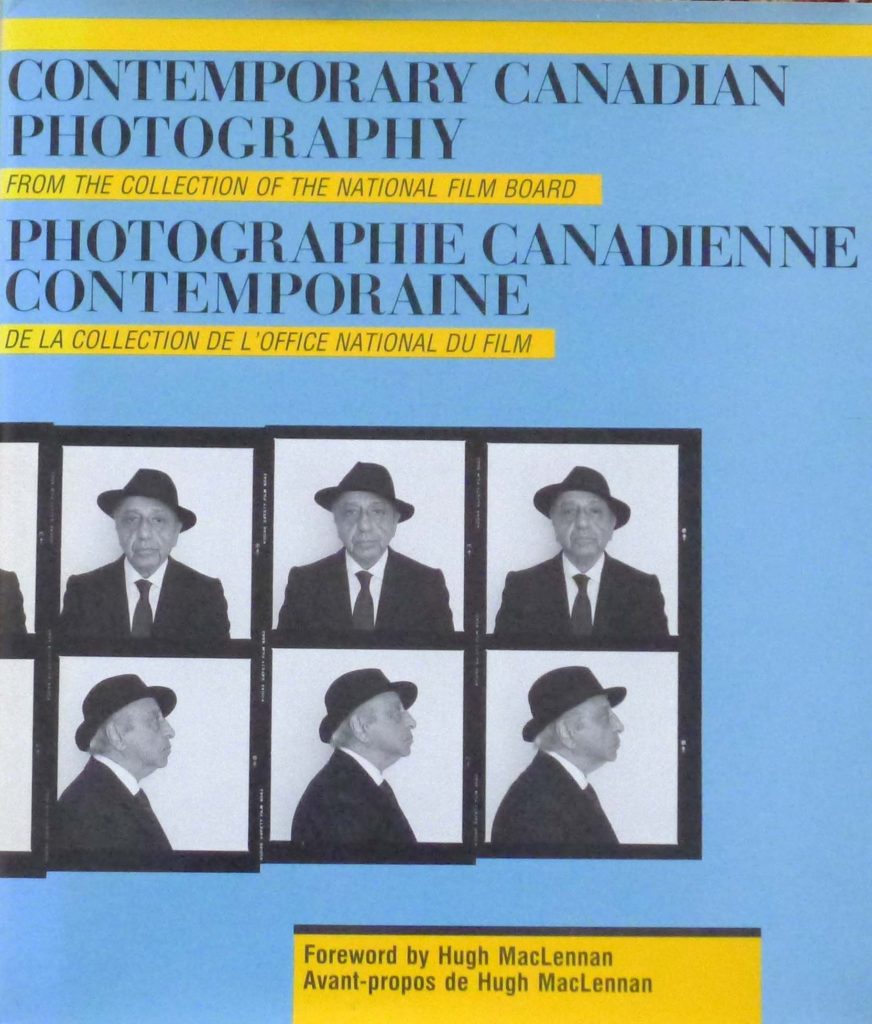

1. Martha Langford, introduction to Contemporary Canadian Photography from the Collection of the National Film Board (Edmonton: Hurtig, 1984), p. 16. The exhibition is an expansion of the selection found in this book.