Aurora Borealis: Meliorist Underground (1985)

Graham, Robert. (1985). Aurora Borealis: Meliorist Underground. In C, 7, pp. 92-93.AURORA BOREALIS

Place du Parc

Montreal

June 15-September 30, 1985

As has been said of the pyramids, that their construction is as much a monument to Egyptian administration as a triumph of ancient engineering, so does this show present both visual delight and a model of organizational innovation. Briefly put, the Montreal International Centre of Contemporary Art, directed by Claude Gosselin, organized a concerted presentation of current art, called “Les Cent Jours d’Art Contemporain-Montreal 85”, of which “Aurora Borealis” is the centrepiece. Persuading four departments of the federal government, four departments of the Quebec government, the Canada Council and several private concerns to provide funding, and the owners of a building complex to lend 40,000 square feet of unused basement retail space, the MICCA has been able to give contemporary art in this city a powerful presence.

Neither a public institution nor a commercial venture, the Centre does not collect or trade in art works but seeks ways to increase accessibility to contemporary art. Both independent and non-profit, it should not need to operate as an instrument of public policy nor fit itself to market demands.

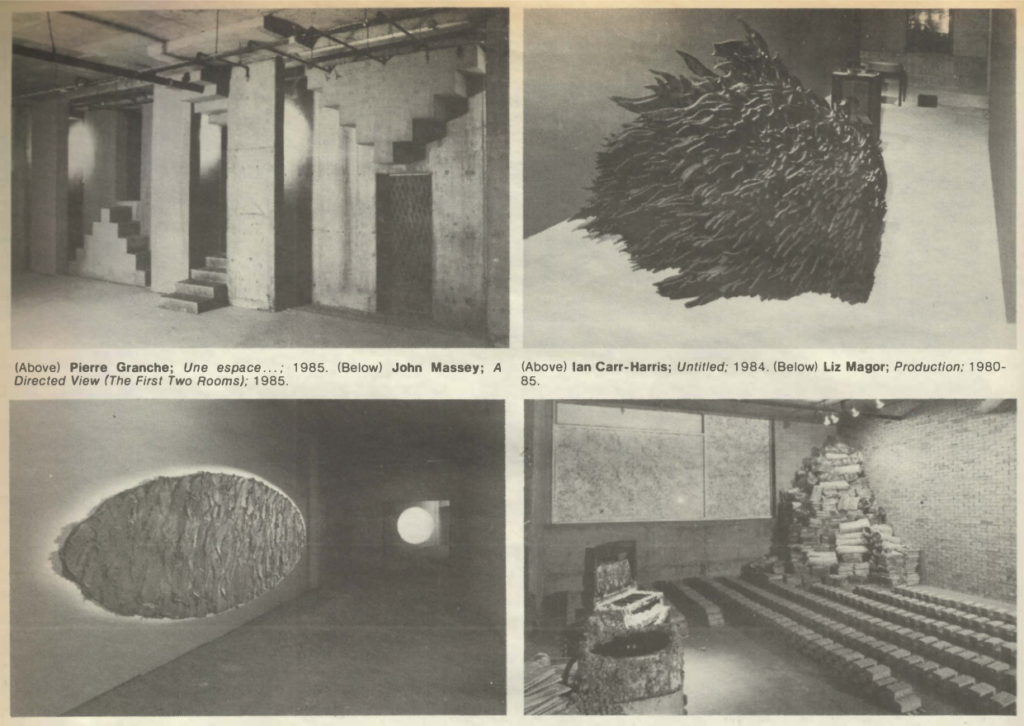

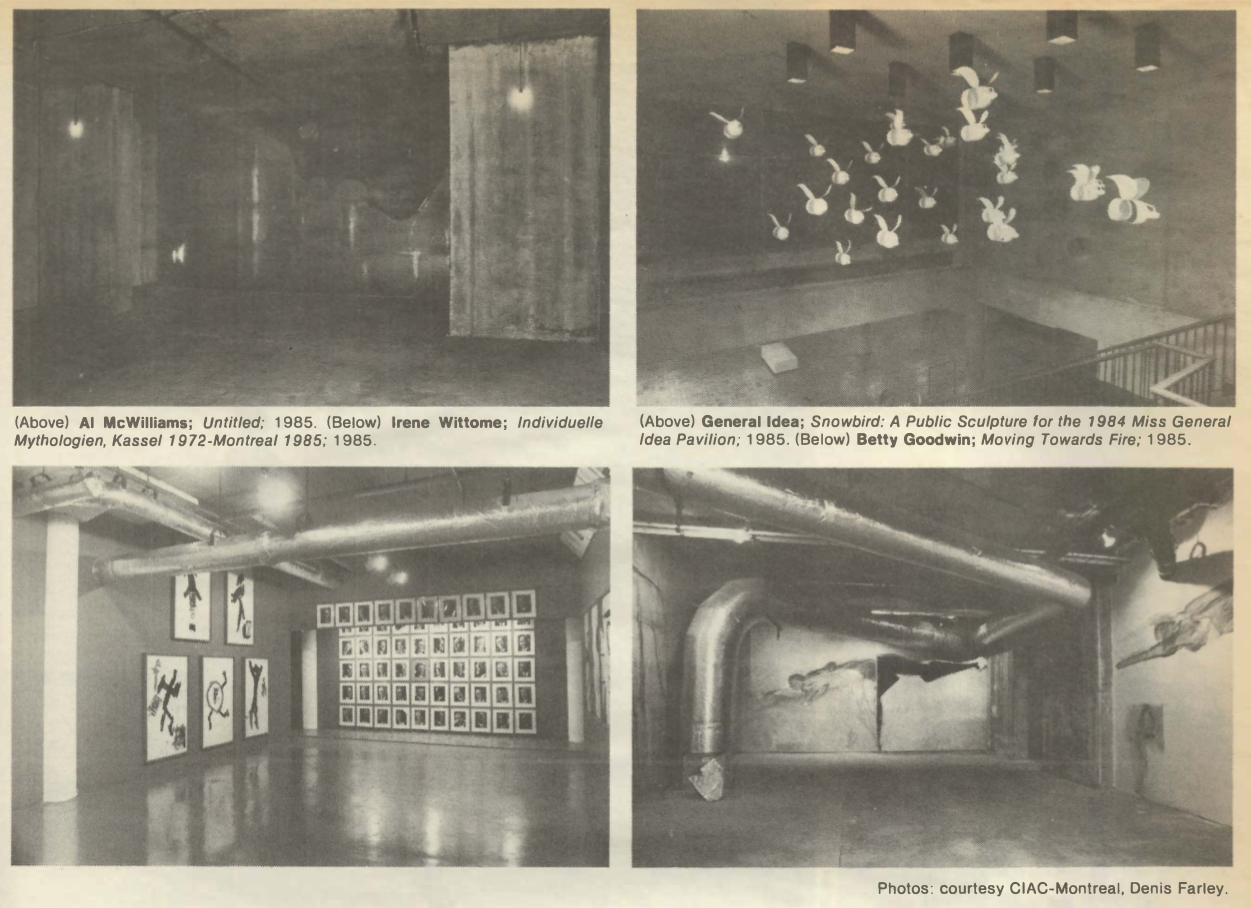

The show itself, curated by Rene Blouin and Normand Theriault, reflects the conditions of its appearance. Choosing to celebrate Installation, they invited 32 artists (that is 29 individuals and General Idea) to assemble 30 works within the generous amounts of space which could be allotted. Installation is a mature genre, with a history and a language, and the artists picked.share in that maturity and established respect. “Aurora Borealis” is not an event of real novelty, bringing forth news from some front of the imagination, but a summarizing of concerns and activities that go back over the last decade and a half. Most of the works, of course, were created and exist only for this occasion, but were all prefigured in the artists’ previous work-thus making for an experience of discovery mixed with a strong feeling of familiarity. While installations are a perfect vehicle for an organization which neither sells nor collects objects, they are also an appropriate expression of another kind of commoditization-the trafficking in the prestige of witnessing exclusive events. “Many of these works,” reads the press release, “will be seen only in Montreal, after which they will be dis mantled.” The rare event comes to replace the rare object.

Above a staircase, General Idea’s Snow Bird: A Public Sculpture for the Miss General Idea Pavilion, is a suspension of 27 carved javex bottles which pokes a sly dig at Michael Snow’s famous Eaton Centre birds as well as honoring the bricolage garden sculpture or patenteaux that appear on summer lawns.

Vera Frenkel’s large and busy installation and sound-slide cycle The business of Frightened Desires (Or the Making of a Pornographer) presents a sweet, facetious assault on Ontario’s censorship apparatus. The gentle demeanour of her persona masks the brick she’s packing.

Michael Snow’s congregation of seven older sculptural works does not present a true, site specific installation, yet together they accomplish a concentrated expression of his critique of perspectival vision. The works of others, like Henry Saxe and Andrew Dutkewych, were also closer to traditional sculpture than installation, while the rusted steel bulk of John McEwen’s Palestine I (the hart) is powerfully offset by the unfinished and rough concrete of its location, establish ing a kind of industrial primitivism.

Among the pieces based on the architecture of the building, Melvin Charney’s From Laugier to Popova: A Portrait in Parts continues his constructed commentaries and recapitulations of built space, in this case extending into a convex window which pro vides the only case of a work employing the vantage of looking in from the street. On the floor below, Pierre Granche built Un espace… with steps and steel mesh which, while visually open, is as unsettling as a cave in its dark restricted passages.

The photo-based works are almost universally projections, using the given darkness to envelop the viewer and present dramatic contrasts. Mixed media pieces operate on the conflict and complexity they can provide such as Ian Carr-Harris’ Untitled which presents the construction of a black-painted plywood ‘fire’ and a soundtrack enjoining the viewer, “Never trust symbols.”

If there is a presiding spirit in all this, it is didactic. Often resembling the displays of public expositions, these artists are transmit ting an attempt to construct neglected forms of knowledge. Historically and generationally, installation was developed by practitioners who approached art as a kind of research with methods unrecognizable to dominant positivism. While the findings are oblique, installation contains the elements of a meliorist, inquiring and teaching art.

In finding and creating spaces for art between the realms of commerce and the institutional repositories, the MICCA is exploring new ways of delivering contemporary art. While occupying the interstices, they enjoin some liberty. But they must also bear the burden of seeking practical success, i.e. respectable attendance, revenues, acclaim, etc., without the institutional ability to shrug off mistakes. In slipstreaming the show with the Picasso and Ramses events, “Aurora Borealis” borrows the kind of promotional tourism these sum mer festivals invoke-a tourism which turns even resident citizens into visitors. A dealer once told me that it took five years for a con temporary art gallery to develop a sustaining clientele. Who, I asked, does the learning? What lessons the MICCA experiences over the next while may shape the organization and direct its activities in ways less appealing than the conditions which spawned this most welcome show.

Robert Graham