Claude-Philippe Benoit’s Survivals (2006)

Graham, Robert. (2006). Claude-Philippe Benoit's Survivals. AXENÉO7 Artists' Centre, Gatineau, Quebec.Norbert Elias, the historian of manners, identified the great “civilizing” change occurring in Western society with, among other indicators, the “transformation of the nobility from a class of knights into a class of courtiers.” In the earlier sphere, violence was “an unavoidable and everyday event”, but the development of a series of social interdependencies replaced a warrior environment with one in which the State arrogated to itself “the monopoIization of physical violence.” 1

But change does not entirely eradicate what was there before. Aspects of the earlier world linger on. There are what Victorian anthropologist E.B. Tylor called survivals: “Looking closely into the thoughts, arts, and habits of any nation, the student finds everywhere the remains of older states of things out of which they arose.” 2 Like the more modern concept of ‘memes’, survivals are the application of evolutionary analysis to cultural symbolics.

However effectively civilization channeled feudal conflict, its memory remains. Isn’t it curious how prevalent feudal forms are in the look and feel of the imaginary societies of video games, even in science fiction versions like “Star Wars”? For feudal societies were both articulated rule-bound hierarchies and yet not entirely civilized. A constant combat readiness was necessary, and combat is the stuff of such games.

In the introduction to his book on face-to-face behaviour, “Interaction Ritual”, Erving Goffmann advocated a sociology of occasions in which the stress of the analysis was placed on the demonstrated dynamic of the event rather than the character or motivations of the individuals performing the event. “Not, then, men and their moments. Rather moments and their men.” 3

Claude-Philippe Benoit displays a similar attitude in his strategy of presenting unpopulated spaces. For Goffmann and Benoit, occasions and locations are primarily ritualistic in character. Ritual spaces or locations function over and above any particular event or set of participants. They are the prepared ground for the roles and behaviours, and meaning of the behaviours, of the incidental human actors, whose actions are often highly codified and set in protocols. Moreover, in the instance of institutional behaviour, there is the necessary fiction that authority and power reside in the office of the organization, and not its occupant. Soldiers are taught that they are saluting the insignia, not the man wearing it.

L’étoffe du prince et son étérnite. In a witty extension of his earlier work on the sites of power, Benoit turns his attention to the accoutrements of power – for what do we call those who administer public and commercial power? We call them suits. And with his usual oblique indirection, he presents not the clothes, but the tailoring. The various Parisian shops are small operations which demonstrate the effect of phenomenological space, as it is lived in and experienced, not just as it is appears. Fully occupied by the tailor’s activity, the spaces are filled with material and tools which, within the tailor’s physical reach, serve as extensions of his engaged body. The tailor, of course, also “serves” the equipment in making the product which realizes the equipment’s purpose; for it is a phenomenological maxim that all appropriation is mutual.

There are also views of the showrooms which, in Goffmanian terms show both “front” and “back” regionalization: they are the public display areas, but they are also where the informal work of measuring and fitting go on. Although we do not see the tailor’s activity, we can sense the prepared script of activity, the various stages and processes, through a broad array of indicators. As Benoit has said, “What I seek are locations that are marked by time, sites of labour that are invested with the best moments of existence, imbued with their traces, possessing an almost material presence.” 4

In one picture we see a tailor’s dummy dressed in a heavily brocaded jacket: the uniform of a member of the Academie Française, itself a prominent survival of 17th century monarchial absolutism. Although a proud “Immortal”, Andre Gide thought the uniform “frightful” 5, a sentiment which confirms that in ritual situations even the most grand must subsume their individual volition and their taste.

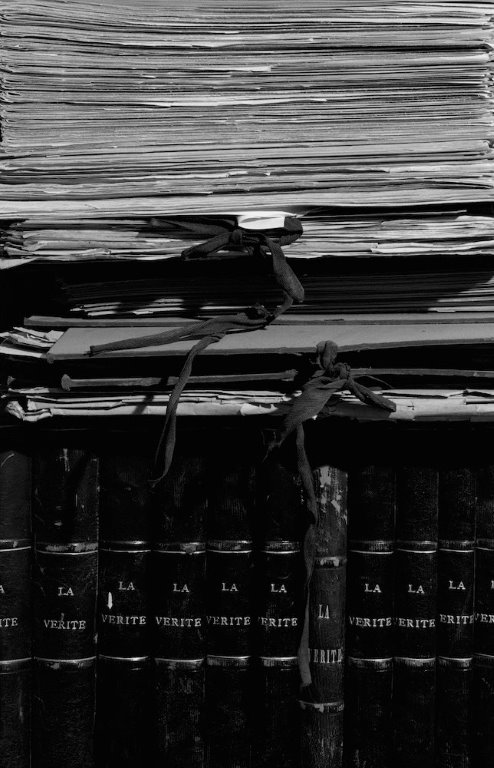

En cour, pour un oui pour un non. Benoit’s photographs from the Supreme Court of Canada and the Palais de Justice in Paris are less forward in showing the location as a place of work, for the fabric of the courts and the physical matter of the proceedings are not the actual business at hand. It is not the job of a court to shuffle documents and move chairs around a table. Yet the real task of the court does require documents, chairs and tables, just as the abstract institution of justice needs its physical institution-token in the form of a courthouse and its attendant activity. In invoking these elements, Benoit is relying upon the rhetorical trope of metonymy, in which a part of an object or an aspect of a concept stands for the whole. Metonyms reduce and substitute. Thus, a pile of dossiers with their ribbons (the original red tape) stand for the record of the debate, the evidence and the argument. Benoit presents a series of nested metonyms, increasing in scale like a line of Russian dolls. The files and books, representing the discourse of the case, rest on long tables which represent a confrontational line of opposition. The empty chairs are for the absent human players of the court’s drama, and the lectern is ready for the speech it supports and stands for. The room itself, in its breadth and features, is the particular representation of judicial deliberation. The total effect of these gathered metonyms is to straighten and stiffen the posture of anyone present in such an environment. All these parts stand for a substantial whole.

Benoit’s images are usually large-sized black and white photographs, natural and representational. Within En cour, pour un oui pour un non he introduces colour images of one or several objects presented in a blur as if caught in motion. Whether these exist as separate punctuating images within the series, or as in the dyptich, L’Accuse, are combined with a dominant black and white photograph, these are fugitive and sensual asides. They mean freedom and are proto-cinematic. This seems to be a possible stepping stone for Benoit in a move away from his more solemn realistic work – a form of subjectivity and corrective play. For as Freud said, it is not the serious that play opposes, but reality.

Societe de ville. While the court and tailor pictures of the interior work show sites of process and represent a scripted ritualistic theatre, the outdoor images are pregnant with inchoate dramatic possibility. Walter Benjamin made famous the observation, “It is no accident that Atget’s photographs have been likened to those of a crime scene.” 6 Benoit’s “crime scenes” are those where the restraints of civilization may be slightly, or more, loosened.

Usually in the distance there is a looming building, perhaps institutional, and which includes on occasion the ancient administrative architecture of the Chateau: vestigial crenellations and parapets representing fortification, now replaced as atavistic privilege. The architectural example of the military fortress turned into luxury residence is analogous of Elias’ civilizing process of knights becoming courtiers, while violence is tamed and replaced by organization. In the foreground the site is impeded by undergrowth, or directed by architectural features – a balustrade, the diagonal passage between buildings – which occupies our vision, making it busy and complex. The eye pauses at the foreground which sets out a terrain of possible activity. What imbues the pictures with drama is their haunting potentiality as activated space.

Some commentators have presumed to identify in Benoit’s work an investigation of the theatrical, arbitrary and “contrived” nature of authoritarian power. I don’t believe that Benoit is ironic toward his subject matter, but rather authentically curious about it. He will, I suggest, disappoint those viewers who are looking for him to illustrate their disaffection toward institutions. Like Michel Foucault, who resisted the notion that power should be understood as a kind of foolishness (“Power is not stupid”, he would say), Benoit presents the mechanics of civilization as invented, yes, but as more or less functioning fragile inventions which include enduring constitutive elements of the pre-civilized past.

While I was writing this essay there was a shooting incident at my daughter’s college. Against an ordered institutional background, a man in a long black trench-coat and appropriating a pre-civilized Goth culture set out in feudal fashion to exact a crude vengeance (itself a crude justice) against those who are bright and loved and who wear pink. It was, among else, a clash of robed identities, of reductive metonymies where clothes are almost heraldic in their identifying legibility. As an extra-institutional, even anti-institutional act, it occupied the negative space of Claude-Philippe Benoit’s concerns and represents the failure of our civilizing rituals and social institutions to channel completely physical violence.

Notes

1. Elias, Norbert, “Power & Civility”, (Pantheon: New York, 1982), p. 236.

2. Tylor, E.B., “Anthropology”, (London: Thinker’s Library, 1930), p. 12.

3. Goffman, Erving, “Interaction Ritual”, (Pantheon: New York, 1967), p. 3.

4. Quoted in Lisa Baldissera, “The Thousand Candles”, essay in catalogue for “Silver: Dreams, Screens and Theories”, (Victoria: Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, 2003), p. 12.

5. Gide, Andre, “Journals 1889-1949”, (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1967), p. 118.

6. Benjamin, Walter, “Little History of Photography”, in Selected Writings, Vol 2, (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 1999), p. 527.